Aug 17 2015

In Memory of Lou — Mick Clarke talks about the late Lou Martin

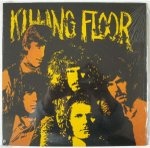

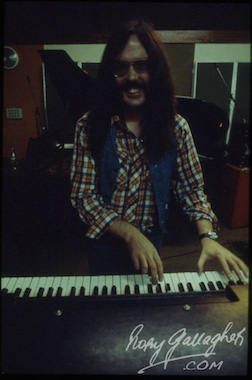

Blues guitarist Mick Clarke began his career with the band KILLING FLOOR, part of the British blues boom of the late 60s. The band backed Texas blues guitar star Freddie King and toured with legends Howlin’ Wolf and Otis Spann. Although short lived, the band released two highly regarded albums which have achieved cult status around the world. One of the original members of the group was Lou Martin, who went on to play piano for legendary Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher.

Following his departure from the Rory Gallagher Band, Lou played in numerous other bands including several featuring his long time friend Mick Clarke including: Ramrod, The Mick Clarke Band, and a reunited Killing Floor. With the 3rd year anniversary of Lou’s passing fast approaching, I got the chance to talk with Mick about those times and his fond memories of a great piano man and great friend, Lou Martin. Here is that interview posted today on the anniversary of Lou’s passing. Thanks to Mick for taking time to do this interview. Be sure to check out his website at: http://www.marshalamp.com/index.html for more information on his latest band and solo projects. And try to catch Mick on his latest tour, you’ll be happy you did!

In Memory of Lou Martin

Shadowplays: Hi Mick, thanks for taking time out to talk a bit about your friend and former band-mate the late Lou Martin.

Mick: A pleasure – thanks for thinking of me, and thanks for remembering Lou.

Shadowplays: You first met Lou when you and Bill Thorndycraft were looking for musicians to form “Killing Floor”. (By the way, a killer of a name for a band, did you have to give Howlin’ Wolf royalties? LOL) Did you include that song in your set?

Mick: Well we did take the name from the Wolf song, but the term Killing Floor goes back to Skip James, and I’m sure a lot earlier. We never played the song on stage.

Shadowplays: Lou answered an advertisement in the music papers. Did he come to your place to audition, or did you or Bill go down to a club to see him play?

Mick: Bill and Mac, (Stuart McDonald, our bass player) went over to his home in South East London to see him. He played a few things on the family piano for them and they were blown away. They came back to me raving about this amazing pianist they’d seen, so we set up a proper band rehearsal, in Clapham. I clearly remember the first time I met Lou – I was sitting in the back of the van when we picked him up from Clapham tube station.

Shadowplays: Lou was a late edition to the newly formed band, wasn’t he? What was your first impressions of Lou?

Mick: I liked him straight away. He was easy going and obviously knowledgeable about blues and rock’n’roll. It was all we talked about really.

Shadowplays: Rory once said that Lou was an important part of Killing Floor’s sound. What did Lou add to your sound?

Mick: Hmm.. that’s hard to define.. excitement, virtuosity, a wild edge..I suppose there weren’t many blues bands in those days that had a touch of Jerry Lee Lewis in them.

Shadowplays: A touch of everything on that first album, from the Honky Tonk Blues piano on “Come Home, Baby” to the almost hymnal harpsichord on “Sunday Morning.”

Mick: The track “Sunday Morning” was of course different to his usual style. There was a harpsichord left in the studio, from, I believe, a Pink Floyd session, and Lou just sat down and played an improvised classical style piece. It sounded so good we had to record it.

Actually Lou’s classical training came through in all of his blues playing – it just had that touch of class.

Shadowplays: How did the first Killing Floor album fare?

Mick: Well not bad considering it was on a small label and was given practically no promotion. It got good reviews, all the radio play that we could have expected, and seemed to get around quite well. It was released in the USA on Sire, which was a brand new offshoot of London Records, so that was a major label. I’ve always regretted not following up the American promotion, as bands such as Savoy Brown and Foghat did.

In later years the two albums both got constantly re-issued (and bootlegged) and have built up a rather strange cult following around the world. I now learn that we were playing proto-punk psycho blues, which we definitely weren’t aware of at the time.

Shadowplays: What’s the story with the track “Lou’s Blues”? What’s going on at the beginning of that track?

Mick: Lou’s Blues.. It was decided that since Lou could obviously play a great piano boogie we should include one on the album, so “Lou’s Blues” was a kind of obvious title. We’d accidentally recorded some between tracks banter which was quite funny, and it was decided to add it to the album, but unfortunately it was also decided to re-record the banter, which is what you hear. I can only say that I was having nothing to do with it.. hence the opening remark “don’t worry about him”..

Shadowplays: Lou left Killing Floor after the first album. Why? Was this around the time he was working on the Krayon Angels project. The Emperor Rosko produced psychedelia project? Was Mac MacDonald involved with that project? Their singer Jeff Pasternak and Emperor Rosko were the sons of famous U.S. film producer Joe Pasternak.

Mick: It was a very intense time. After we’d toured with Freddie King we felt that we should have seen some progress in the band’s career, but it wasn’t forthcoming. We were all a little hot headed in different ways, and the tempers flared and the band split. It was just frustration really in not making the progress that we felt we should be making. After a while we carried on as a four piece with various other musicians, but Lou was then busy with other projects.

Yes, Lou and Mac both did the Emperor Rosko project.

Shadowplays: Lou wasn’t involved with the 2nd KF album except for ‘Call for the Politician’? That became a reasonably successful single didn’t it? Except for that one song, why no Lou on the album?

Mick: Well yes, Lou was off doing other things by then but we were still friends. Lou was brought in to add a bit of piano to “Call For The Politicians” because it was the single, but to be honest you can barely hear him.

“Call For The Politician” was released on Larry Page’s label “Penny Farthing” so we got the full pop record promotion of the time.. appearing on Radio One’s lunchtime show for example, and later on the fore-runner of the “Old Grey Whistle Test”. “Politicians” bubbled under the charts for a while but didn’t break through. It sold quite a few copies in Germany, but nobody told us!

Shadowplays: How would you describe Lou’s style of playing? Barrelhouse Blues? Jerry Lee on steroids? He seemed to be able to play a wide variety of styles. How did he fit in with the group?

Mick: Lou told me, quite specifically, that his influences were Jerry Lee Lewis, Memphis Slim and Fats Domino. So you could say that would be wild rock’n’roll, high speed blues soloing and good time boogie respectively, but crucially mixed together with Lou’s own temperament and personality, producing something unique (and explosive). I think I’d say that there was a fair measure of Otis Spann in there as well – a great feel for straight ahead Chicago blues. It gelled immediately with the band.

Shadowplays: Was Lou the story teller in the group as he was in the RG band? If there was a story to tell it was usually Lou doing the telling. What would be the great story that Lou would tell about you, Mick, that would have us all in stitches?

Mick: Brilliant question, but I’ve no idea – you’ll have to ask another of his friends. But actually, I don’t remember him ever telling stories about other band members – they were more reserved for people outside of our immediate circle, who he might meet on the road. Lou’s story telling grew over the years as he had more and more experiences to tell about.

The kind of story I remember from Lou was one about a rock’n’roll festival in Europe that he played on, where someone jumped on a grand piano as part of the act, fell through and got stuck while still having to sing and carry on the act. Sounds quite amusing now, but when Lou told the story it was hilarious, partly because Lou couldn’t control his own mirth in telling it. As you say, we’d be in stitches.

Shadowplays: Former Radio Caroline DJ, John Edward became your agent and got you bookings at places like Middle Earth, and the California Ballroom in Dunstable, getting you guys support gigs for bands like Ten Years After, Jethro Tull, etc. “The Cali” was a huge place, wasn’t it? I understand there was a balcony overlooking the main stage and disgruntled patrons could pour their beer out on the musicians. Any remembrances from those days at The Cali or Middle Earth, etc.?

Mick: I don’t remember the beer pouring business, but I certainly remember the Cali, as we played there with numerous big acts of the time. These included Jethro Tull and Ten Years After, but the one that sticks in my memory is Junior Walker and the All Stars. It was great to see a real American R&B band like that, and his sax of course was fantastic.

Shadowplays: You also got to jam with Paul Kossof and Simon Kirke while they waited for their tour to start up. Was this when they were with Black Cat Bones, or Free?

Mick: Yes, another time we jammed with Koss and Simon Kirke. They’d just signed with Island and had about six weeks to wait before the gigs began – a long time when you’re at that age and really want to work. We knew them already, so they came along to our gig at the Pied Bull in London and sat in – Koss got up, plugged into my amp, turned everything up full and blew the room away. One of the few times I’ve been blown off stage by anyone, but I took it as a lesson. Koss’s total intensity was what made him one of the greats.

Shadowplays: John Edward was also the producer for the first KF album. Edwards was also the agent for other SE London groups such as Katch 22, Geranium Pond, Dr. Marigolds Prescription, Wilsons Transaxion, Magic Mixture, Toast, Pandamonium, Mint Tulip, Army, Mable Greer’s Toyshop. Do you remember any of these bands? Looking at their names, “Killing Floor” was a darn fine name for a band!

Mick: Most of John’s bands were pop groups – we were the oddity. We did play a few dates with Katch 22 and Toast – notably the British Rail Beat Cruise, on a boat going round the Isle of Wight! It was actually a great gig – we enjoyed it.

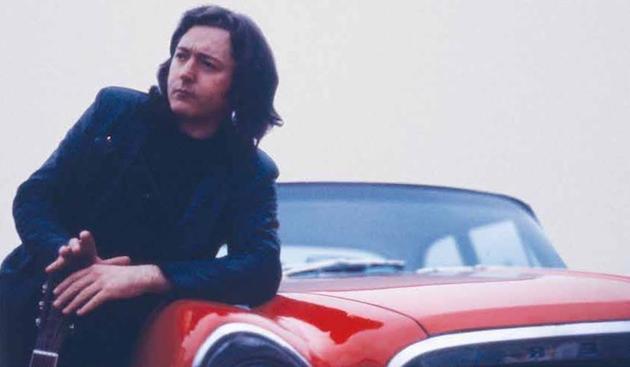

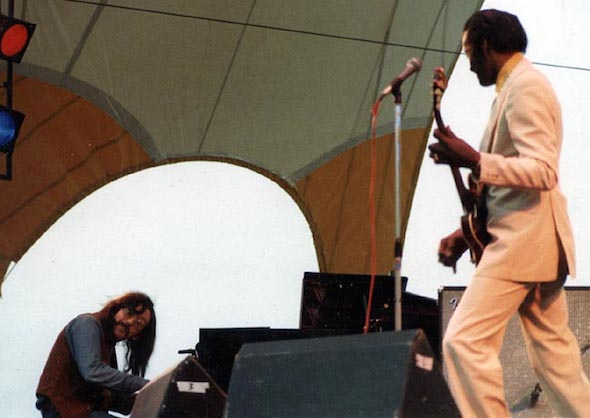

Lou jamming with Chuck Berry Photo ©David Cooper

Shadowplays: Killing Floor gets an offer to tour with Freddie King. Originally it was supposed to be a tour with Howlin’ Wolf, wasn’t it? Did you ever get to play with Howlin’ Wolf and his guitar man, Hubert Sumlin? Howlin’ Wolf was a very aggressive performer on and off the stage.

Mick: Well these guys like Wolf and Freddie were coming over on tours and needed backing bands. John sorted out the Freddie tour for us, which was great. I don’t know if it got changed around or not – anyway, I was happy. Freddie King!!

So we had a couple of great tours with Freddie and it was a huge learning experience for me. And we got to meet the Wolf. He was OK – quite chatty, although he had clearly been ripped off a few times in the past and was very wary of people.

We played a gig with Hubert a few years ago, so it was great to meet him. A very amiable guy. Somehow I got the job of tuning his guitar for him before the show, which I did with great care. However he never made any further adjustments during the gig so by the end it was going well out of tune and I was starting to feel very uneasy! Anyway, he wasn’t bothered – Mister Easygoing.

Shadowplays: So how did the gigs with Freddie King go? What are your fondest memories of those gigs with Freddie?

Mick: It was nice that after a while I got into a little routine with Freddie, where he’d play a riff and I’d copy it. After a bit he’d play something that was impossible to follow. I’d shrug and walk away and he’d give me a big round of applause from the crowd. I also spent a bit of time with him – we went to the pictures together once! Very bizarre. But I didn’t really get close to him – he was a lot more mature than me – I was just a kid.

Shadowplays: You mentioned a bit of Otis Spann in Lou’s playing style. I imagine Muddy’s keyboardist Otis Spann would have been a hero of Lou’s. I read somewhere that Lou and Otis had a sort of “battle of the keyboards” one night after a gig.

Mick: Yes we did some dates with Spann and went to a party together one night, up in Newcastle I think. Spann sat down at a piano and played, which was wonderful. Then Lou played some boogie – I think Spann was favourably impressed. Nice guy – liked a drop of whiskey.

Shadowplays: Lou left the band after the Freddie King tours? When did future RG bandmate Rod De’Ath join Killing Floor? How did you know Rod, through Lou?

Mick: Yes I think.. (it was a long time ago).. I think Lou had been in a band playing progressive music, and Rod was one of the two drummers. We became friends and it was clear that Rod had a love of the blues, and could play it very very well. Later Gerry McAvoy turned up at Rod’s house to take a room for let – that was how the whole Gallagher connection started.

Shadowplays: After the break up of Killing Floor, some of the band members joined Cliff Bennet’s “Toefat”. How did that come about? Did Lou know Cliff from before?

Mick: Lou had also – (he’d been busy) done some cabaret gigs with Cliff, doing the old “Rebel Rousers” hits. So when Cliff decided to reform a version of Toefat, he recruited Lou. Lou recruited me and I recruited the rest of Killing Floor.

Shadowplays: And then shortly after Lou was recruited by Rory. Were you familiar with Rory’s stuff? Were you a fan?

Mick: When Rory first came over from Ireland he played at the Marquee Club in London, and all of Killing Floor went along to see this new blues guitarist. I wasn’t immediately impressed – he played a lot of notes and with great energy, but I was more into the “less is more” philosophy at the time – Peter Green, Kossoff etc. However the crowds took to him without hesitation and his career took off very quickly.

The next time I saw him the whole show was far more refined and professional and I was very impressed. I particularly remember his use of dynamics – dropping down so low at one point that I think he turned his electric guitar right off. Then coming back with a blast of power – if I think about using dynamics in a show I still think of that moment.

Shadowplays: Did you all ever share a bill either with his band Taste or the Rory Gallagher Band? Maybe at the old Marquee?

Mick: No we never shared a bill with Rory until the Bonn Blues Festival in the 90s.

Shadowplays: And what did you think of Rory’s desire to add a keyboardist to his 3-piece?

Mick: I don’t remember really – it seemed quite logical to add a great player like Lou to the line-up. I was a bit miffed at the time because we’d just formed the new Toefat and now we had to try and replace Lou! We got a guy named Lynton Naiff in the end who was a great player and became a good friend.

Shadowplays: After Lou’s days with Rory ended, you teamed up with Lou in the band Ramrod. Had your latest band, SALT, already broken up, or were you doing both bands concurrently?

Mick: SALT had been very successful on the club and college scene for a couple of years, but it was now punk time! We were almost punk but not really, so we were put in the “boring old farts” category, and there didn’t seem to be much future in it.

We had had regular jams with Lou and Rod during the Rory years (one time with Rory himself involved) so it seemed logical to form up with them and get a new band together. There was a lot of talk about taking the band to America but it never happened. I think if we had done we would have had some success – I went over there anyway by myself, and bands like Ramrod were doing OK. Anyway – it’s history now.

Shadowplays: I’m always curious how these bands get their names, where did the name “Ramrod” come from? The Duane Eddy song? The Veronica Lake movie?

Mick: There was a London beer, I think – “Ramrod and Special”. It came from that.

Shadowplays: RAMROD opened up for Muddy Waters? Did you guys get to hang around with Muddy? I think I read that you had met Muddy before with SALT? Was Pinetop Perkins with Muddy at that time? Did Lou get to jam with Pinetop?

Mick: SALT played at the New Victoria Theatre in London with Muddy on his first big London concert. It was a great night. So when he returned we managed to get Ramrod the support spot – this time at the Rainbow. It wasn’t the same buzz though – we had to play while people were still finding their seats, and all the lights were up. Harvey Goldsmith, the promoter, was apparently running around backstage saying “who is this band? This ain’t the blues”!

However we did get to meet Muddy after the show. He asked who was playing the harp..(Stevie Smith) and said he’d ask for “my boys” next time he came over. Nice man.

Yes Pinetop was on piano and what I remember was that we were all at the side of the stage during Muddy’s show, and Pinetop was smiling across at us and we had a kind of little “gig within a gig” with him. It was a good atmosphere. I don’t think Lou ever jammed with him – not that I know of. Though of course Lou toured with Muddy afterwards when he was backing Chuck Berry, so who knows.

Shadowplays: You left Ramrod after a US tour fell through? When did you next meet up with Lou?

Mick: Well, as I say, the big Ramrod move to the States never happened, and I didn’t feel there was much future in the band staying in the UK at that time. I actually went and lived in Los Angeles for a year, and when I came back I’m sure one of the first things I did was meet up with Lou for a pint.

Shadowplays: Didn’t Lou open for the Mick Clarke Band a time or two? I understand that at one time Lou would do solo shows as warm up for the headliners.

Mick: A few years later when the Mick Clarke Band was starting to do quite well in Europe, we had a Swiss agent named Markus Gygax, who was a huge fan of Rory, and Lou. So Lou was recruited to open for the MC Band on several European tours – all over Central Europe.

Lou was playing solo piano and singing – all his old favourite blues and rockers such as “Six Days On The Road” and “High Heal Sneakers”. He wasn’t a great singer but made up for it with sheer enthusiasm, so his act always went down well, and quite often he would join the MC Band later for a jam.

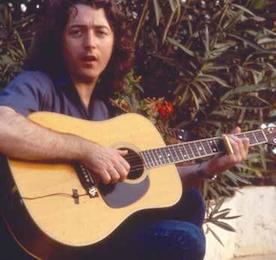

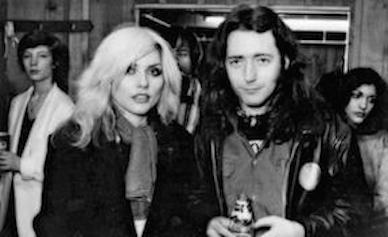

Lou Martin, photo courtesy of Gerry Gillard

Shadowplays: After Lou’s stint in the Scottish Blues’n Trouble band, he start playing for you again. And there was a duet album? How did that one come about?

Mick: Yes at a later time when the job became vacant and he was free, Lou joined the band fully for a couple of years. Also around that time I got the idea of doing a duo album with him, and Burnside Records in the US were interested, so we recorded “Happy Home”. It was a lot of fun and we went on to tour Scotland a couple of times, Ireland, Northern Europe and some one-off festivals and clubs. It ran its course after a while, but I’m sure if Lou was around now we’d still be doing the odd show.

Shadowplays: Any good Rory stories from Lou?

Mick: Lou always spoke with great respect about Rory. I think with Lou if you did the job right – played real music with integrity and honesty, then you were all right. And of course Rory certainly fitted that description. There were plenty of stories from the road, but as I say, usually about people outside the immediate band.

Shadowplays: After his time with your band he started working of all places a flower shop while also playing piano in a local pub. Did you stay and touch?

Mick: Lou had an interesting and varied private life, and yes, at one point he was living with a florist and working in the shop. I’d phone him and he’d be in the middle of making a wreath for a funeral.. but Lou always adapted very well to changes in circumstances. It would be a shrug.. “oh well”.. and get on with it.

Shadowplays: Before Lou’s passing, you reformed Killing Floor, did you try to recruit Lou or was he already too ill to do a possible reunion?

Mick: Lou came and played on the re-union album, “Zero Tolerance”. He would have been on the concerts that we did but by that time he’d had his stroke, so it wasn’t possible.

Shadowplays: What is your favorite memory of Lou?

Mick: For some reason the memory that always comes to mind was going up to see a Rory concert at the Hammersmith Odeon. I found Lou in the pub next door, pint in hand, surrounded by friends and fans, beaming and full of health, looking forward to doing another great gig. Exactly where he wanted to be, and at his peak.

Shadowplays: What did Lou mean to you, as a musician and as a friend?

Mick: I was very privileged to have known Lou – he brightened our lives with his personality, and his musical legacy lives on.

Shadowplays: Mick, thanks for taking the time to talk about Lou Martin, a great piano man and, I’m sure, an even greater friend.