Jan 21 2014

Between the Bombs

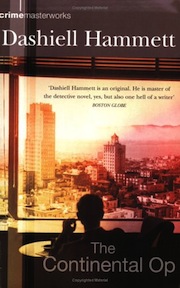

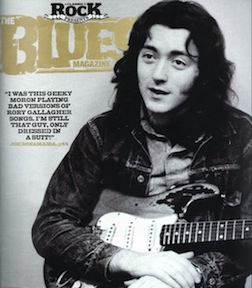

In the November 2012 issue of Classic Rock’s The Blues Magazine, Gavin Martin penned a wonderful article about Rory Gallagher and his rise to prominence in war-torn Belfast, his refusal to abandon the much-bombed city while other bands fled like rats from a sinking ship, and his triumphant return to the city for the making of his landmark album and film, Irish Tour ’74. Special thanks to Matt at Blues Magazine and author Gavin Martin for giving permission to re-post this excellent article. Be sure to check out Classic Rock Blues Magazine’s presence on facebook: The Blues Magazine, and writer Gavin Martin’s website, Talking Musical Revolutions and his facebook presence at Talking Musical Revolutions on FB

Returning guitar hero RORY GALLAGHER brought hope and musical inspiration to his war-torn spiritual hometown of Belfast. The Blues goes behind the barricades to bring you the story of the making of the landmark album and film, Irish Tour ’74

“While Ulster teetered towards the brink,Rory’s Rock hit with righteous affirmation”

By 1974, Belfast, the Northern Irish city Rory Gallagher had, five years previously turned into a rallying point and springboard to international fame, had changed. Changed utterly — with a lot of terror and precious little of the beauty poet W B Yeats saw after the 1916 uprising, in Ireland’s other capital, Dublin.

Dreams of glory and freedom had coursed through Belfast back in the halcyon 60s. But they had halted with the outbreak of the troubles in 1968, and the subsequent arrival of British Army on the city’s streets.

But there were those who remembered pre-Troubles Belfast as a bohemian and musical hotspot. In the 60s, Dublin was far more under the sway of the show bands and pop. Belfast’s hardcore blues and jazz scene, steered by such characters as redoubtable record shop owner Dougie Knight and piano-playing blues supremo Jim Daly, ensured it to be the city where the action was.

Gallagher had gone right to the centre of the city’s heat with his new beat group Taste, when he arrived in Belfast in 1967, on the cusp of his 19th birthday. Even for the ‘look Ma, hair down to the collar!’ style of the times, Rory’s wild flowing locks stood out.

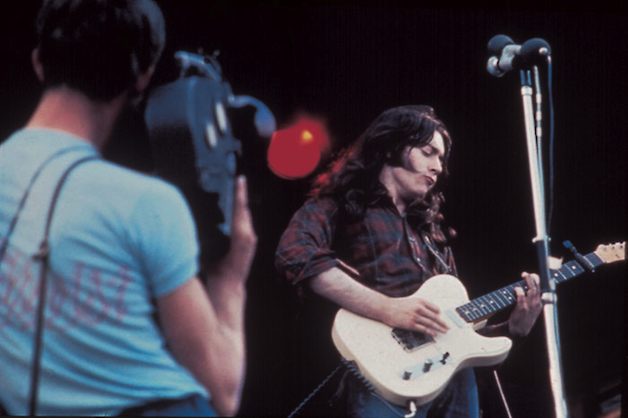

As did his extraordinary talent. Brandishing his 1961 paint-stripped, Sunburst Fender Stratocaster, Rory fronted the Cork-originated Taste at Belfast’s Maritime, an old Seaman’s Mission turned rhythm and blues club mad famous by Van Morrison and his band Them.

With Morrison preparing to leave for America to record Astral Weeks – his historic, melancholic farewell to ‘the old’ Belfast – Gallagher arrived, set to be crowned Ireland’s multi-instrumental electric guitar warrior king. And so it came to pass, after Belfast Rory moved onto London, then the world.

By 1974, Gallagher was a star touring the world’s venues, regularly upstaging arena headliners on coast-to-coast American tours; and admired by Clapton, Hendrix, Lennon and Bob Dylan. But, unlike the great and good of rock’s emerging aristocracy or the exiled Morrison, Gallagher played annual Belfast shows.

History recalls the early 70s as the time when Jimmy Page made America shake to its knees, when ‘Clapton Is God’ graffiti was pated on gable walls and Townshend windmill-mapped the world between Tommy and Teenage Wastelands.

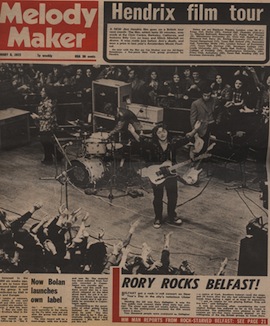

But for a snapshot of The Real Rock Blues as a communal healing ritual, the January 1972 cover picture on the now-defunct Melody Maker, showing Rory onstage with jubilant and sated fans at the end of his Ulster Hall ’72 New Year show, was hard to beat.

During that run of shows, the now solo Gallagher and his new band became the first group to play in his adopted city since the Troubles began; at a venue on the notrious ‘bomb alley’, also home to The Europa, soon to earn the title of the world’s most bombed hotel. Others had ceased playing the city, arguably when their music’s power was most needed. The passionately wrought piece by the late Roy Hollingworth that accompanied the Melody Maker cover photo perfectly summed up the importance of Gallagher’s shows.

“It was something bigger, more valid than just rock’n’roll,” Hollingworth wrote. “I’ve never seen anything quite so wonderful, so stirring, so uplifting, so yours as when Gallagher and the band walked onstage. The whole place erupted. As one unit they put their arms into the air and gave peace signs.”

Small wonder that in 1974, with the Troubles lurching towards what would be one of its most perilous and murderous periods, Gallagher decided to call on film maker Tony Palmer to document that year’s tour of the country where he was born.

Certainly before (and pretty much after) booze and prescription drugs put him on a downward spiral to early death, it is impossible to find anyone with a cross word for Gallagher. The shy, thoughtful, gently spoken man who turned into the most dynamic performer onstage was hardly the archetypal guitar god.

But Gallagher, the people’s guitarist, was well aware of his power to unify the community. In the film Cork and Dublin would feature but it was in his adopted city of Belfast that Rory would make his most notable stand. That surely was uppermost in his mind when he decided to capture the Belfast performance for posterity.

“Belfast had a special place in my heart,” recalls Gerry McAvoy. “I’m a ‘Beal Fearstian’ and Rory regarded it as his second city, his second home.”

McAvoy was foot soldier on Rory’s bass-line, from the making of his 1971 self-titled solo album until 1991, his departure coming three years before Gallagher’s early death caused by complication after a liver transplant in June 1995.

“Rory loved Belfast. Just loved it,” continues McAvoy. “Anytime we hit the stage after 1971 you were aware that, apart from the odd cabaret turn at the Abercorn (site of a 1972 bomb blast killing two and injuring 130), none of the bigger bands would come back to play Belfast, it was starved of music. Obviously after The Miami Showband tragedy it just got worse. We’re professionals. We play as well as we could wherever we played but it was a special situation in Belfast, something you could never acquire or attain at any other gig.”

The horror of the Miami Showband Massacre in 1975 – the cold-blooded murder of three and maiming of two members of the Miami, then the most popular showband in Ireland — on a country road in the dead of night after a gig, plunged the prospects for music in Northern Ireland into the abyss.

Even by the atrocity standards of the time, the horrible callousness of the attack was dumbfounding. Attempting to place a bomb on the groups minivan after stopping them at a bogus checkpoint, two gunmen died when the bomb exploded unexpectedly.

The two more opened fire on the band. Such was the horror of the times.

But Gallagher still remained, returning to play Belfast each year, the bristling performances captured on the Irish Tour ’74 film and accompanying live album, a testimony to his valour and persistence.

Gallagher seems almost predestined to take on the role of music warrior fighting the good fight with his six-string, while the weapons of war raged all around. A calm and meditative Piscean, he was born near a river where his father laid electric cables. Right up until before his death, when he resided in London’s Chelsea Harbour, Gallagher favored living by the water.

His birthplace, Ballyshannon, is in Donegal, the most northerly county in Ireland (although, in a curious ‘joke’ played by the British partition of Ireland, located in the southern Republic after the country’s 1922 division) but, befitting an all-Ireland hero, he was raised in Derry and Cork.

Quickly finding his fingers as a teenage guitar-playing dynamo, he transmuted the influences of Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, Big Bill Broonzy and many more to become an instant musical hero for Irish youth.

He caused equal amounts of sensation and outrage when he had first appeared, wild locks a-flowing and the licks flying, on local RTE TV fronting The Impact.

In Belfast, The Maritime’s former status as an old seaman’s mission chimed well with Gallagher’s preference to be near water. And, true to form, he turned the room into a sea of sweat-drenched blues glory.

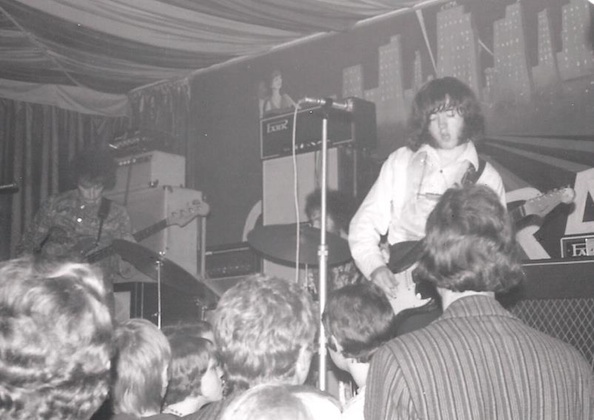

Taste at Club Rado ©Blair Whyte

During the time Taste played The Maritime, Gallagher and the band lived down the coast in Ballyholme, near to where I was growing up. In the morning, mysterious sounds, great arcs of electric guitar, were heard over the neighborhood. My six-year-old self was simultaneously confused [this was the same instrument that played on the records at home?] and excited beyond all reckoning. Not least when my father and sister told me that this local star was going to become to the electric guitar what George Best was to football.

In the evening, more than once, there was Gallagher, perched on the wall by the promenade in his check shirt. Just sitting there, looking out at the sea. Perhaps he knew that, for Celtic mystics of old, meditation on water was a pathway to define future intention. Perhaps he was just planning his next move.

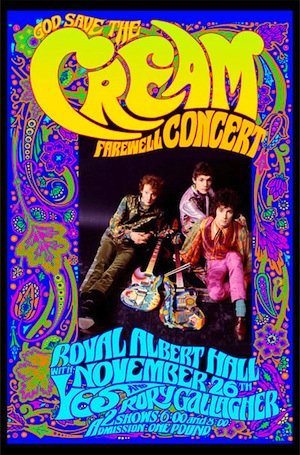

It was a year later, in 1968, while filming Cream’s Farewell Albert Hall concert, that director Palmer had first seen Gallagher. The guitarist had formed Taste in Cork, but the lineup had changed during the time he spent in Belfast. Coming under the wing of manager Eddie Kennedy, Gallagher was persuaded to axe original drummer Normen Damery and bassist Eric Kitteringham in favor of John Wilson and Charlie McCracken, the ace rhythm section from Belfast’s acclaimed band of the moment, Cheese.

Eric Clapton later credited Gallagher’s exuberant and anguished, vibrant and visceral tone for getting him back into the blues. John Lennon had spread the word on Gallagher’s brilliance after attending an early Taste show at London’s Marquee. After the group laid waste to the 1970 Isle of Wight festival (captured on a subsequent live album), a below-par Jimi Hendrix, drolly but pointedly, remarked “ask Rory Gallagher” when queried what it felt like being the world’s greatest guitarist.

Palmer recalls being brushed aside by Cream’s manager Robert Stigwood when he suggested filming Gallagher at the Albert Hall in ’68. It’s hardly surprising that Stigwood, an impresario with no financial interest in the young Irish comet, wanted the job in hand, guitar god Eric rather than warrior king Rory, to remain the director’s focus.

Still, Palmer’s interest was piqued.

“I just went back and introduced myself, he was very nice and very polite. I said ‘I want to congratulate you — what I heard on the first set was really extraordinary and I’d love to meet up some other time’.”

By 1974, Palmer’s status as a pioneering director of rock music on screen was well advanced, with the Cream film and the John Lennon favorite, All My Loving, Irish Tour ’74 and his Leonard Cohen documentary Bird On a Wire show how he was seized by the momentum of rock’n’blues in a period where experimentation, individuality and transcendental artistry intersected.

Departing his BBC staff job in 1971, Palmer increasingly looked to rock musicians to examine the great themes and practicalities of performing music explored in his earlier classical and opera-themed documentaries, including a look at contemporary composer Benjamin Britten.

“Out of the blue, about mid-1973, I had a call from Donal [Gallagher’s younger brother, confidant, manager and now custodian of the legacy] saying Rory was going to do a tour of Ireland.

“He said ‘Ireland’ very pointedly, did I think that would make an interesting film? I said yes and asked where he was playing.

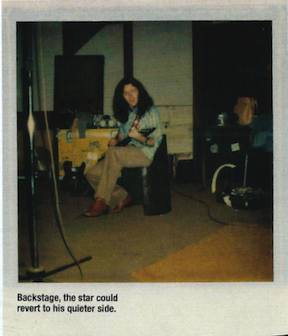

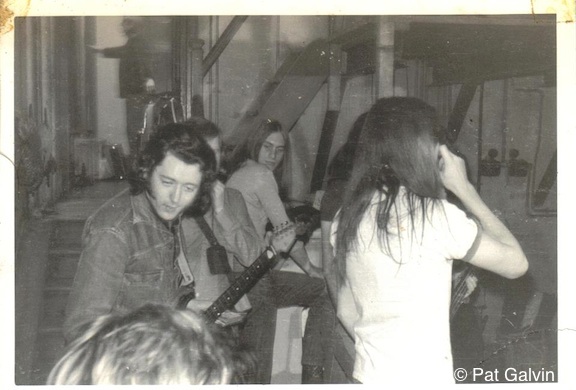

Backstage during the making of Irish Tour ’74. Photo by Pat Galvin

“The answer came he was going to play Dublin and Belfast. This was right at the height of the Troubles. I though ‘this is a very interesting proposition’.”

Interesting enough for Palmer’s former employers at the BBC to jump at the chance to have first screening rights. Palmer met Gallagher to talk about the project soon after Donal’s call.

“Rory was at pains to point out he wasn’t active in any sense politically. But he felt very strongly that he should be allowed to play in Northern Ireland and the Republic because to him there was no real difference, except in terms of government.

“He said, ‘I don’t want to make a movie with any political content but it will be self-evident’.

“I said ‘fine’, I wasn’t’ going to be making a political film.”

McAvoy remembers Gallagher downplaying the size or nature of the project to the band in rehearsal. “He was pretty flippant, he didn’t want to make a big deal of it — ‘we might bring a couple of cameras along’.

“But we knew we were going to record it for an album, or an LP, as they said in those days.”

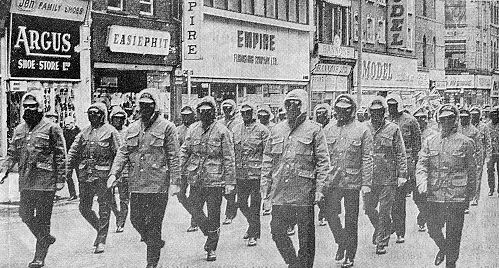

The film crew arrived in Belfast just weeks after the country’s ruling Unionist politicians and associated paramilitary factions met at the Ulster Hall to advance plans for what would become that May’s Ulster Workers’ Council Strike.

During it, my father and other non-sectarian trade unionists pleaded with the Secretary of State Merlyn Rees, then in charge of day-to-day running of the country, to provide protection for intimidated workers. It was all to no avail.

The strike would bring the entire country to a standstill during its two-week duration; succeed in its aim of toppling the power-sharing Sunningdale Agreement; and result in the deaths of 39 people (including 33 killed by UVF bomb lasts in Monaghan and Dublin, dramatically bringing the Irish conflict to the Republic).

May’s Ulster Workers’ Council Strike — 1974

Such was the perilous climate under which Gallagher’s New Year Ulster Hall performance took place. As without he 1971 shows, certain informed sources had always given a broad indication that, even while bombs exploded around the city, Rory’s gigs would be spared unwanted incursions from the terror campaign.

“It was pretty heated,” says McAvoy. “There was a little fear there, but once you got into the swing, it was, okay,”what’s going to happen is going to happen’.”

Perhaps, but when Palmer’s flight landed in Belfast it was made clear that he and his crew were of interest to the British authorities. “We were met by Special Branch officers who came up to us and said, ‘We know why you are here’.

“I said, ‘jolly good’. They said, ‘We are here to make sure you are okay. I said, “Well, fine, I don’t think we’re anticipating any trouble’. He said, ‘No, but better to be on the safe side.’ As far as I know, they tailed us all the time we were in Belfast.”

McAvoy recalls the making of Irish Tour ’74 as a high for the band as a unit with Rory having a relatively relaxed attitude. But Palmer noted signs of nerves, in line with the fastidious, eventually neurotic, disposition that would — in tandem with the self-medicated toll taken by prescription drugs and Too Much Alcohol – characterize Gallagher’s later years.

“Rory was quite worried about the concert in Belfast. There had been a very nasty explosion two weeks previously, probably the work of the IRA, and he though he might get the back end of that when he went on stage.

Backstage with Rory Gallagher during the making of Irish Tour ’74, ©Pat Galvin

“Some of the scenes that you see in the film in the dressing room, that’s the reason — it wasn’t just the general nervousness of going on stage. He wasn’t quite sure what the reception would be. I think Rory was more nervous than we were.”

The next year, Palmer returned to Dublin to film rebel songs in a hard-line republican hostelry.

“After we’d finished, this guy came up and said, ‘It’s great to meet’cher again.” I said, “Wait a minute, we’ve met before?” He said, ‘Oh yes, when you were filming Rory Gallagher in Dublin we were looking after you.’

“I’m glad I didn’t know,” chuckles Palmer.

Backstage in Belfast and on stage at rehearsal in Cork, Gallagher displays his musical weapons of war, including a steel guitar and his paint-stripped 1961 Fender Sunburst. He explains how harmonica holders worn round his neck have scratched the paint off the bodywork of the Fender. But the paint-stripping process was, and over the years ahead would further be, compounded by the high alkaline content of his sweat acting on the instrument. The perspiration was itself a function of the rare blood group that made it difficult to locate a liver for the transplant operation that would lead to his death.

Gallagher’s music was his heart and soul; he literally put his blood and sweat in it.

“That was the nearest to a political statement he got,” ventures Palmer. “By that tour he was trying to say something politically, ‘You lot have got to get yourself together and stop bombing the hell out of each other. That’s not the way forward.’

“But he didn’t want to make it propaganda. It was a film about him as a phenomenal musician, contrasting the bravado and bravura of him on stage with the completely self-depracating guy who you’d pass in the street and not think twice about. He was so diffident personally and incredibly self-effacing about his incredible skills. He didn’t think there was anything unusual about it, he just though ‘that’s what I do’.”

Palmer’s movie, and the accompanying Irish Tour ’74 live album, captures the outfit comprising McAvoyu, Belfast keyboard player Lou Martin and the splendidly named, skin-shredding Welshman Rod De’Ath at a towering peak.

Only McAvoy remaind from the band featured on Rory’s listening 1972 Live in Europe album; the addition of Martin’s keyboards highlight Gallagher’s growth as arranger and band leader.

Tantalising excitement reigns on the dynamically blistering Walk on Hot Coals. Alongside crowd-rousing triumphs Going To My Hometown and Cradle Rock, Tattoo’d Lady, Rory’s song of faith in and commitment to the minstrel troubadour life, rings with the clarity of a mission statement.

The euphoric freak-out Who’s That Coming and the lambent shimmer of the majestic A Million Miles Away compare with similar jazzy progressions on 1974’s Out of The Storm by Gallagher’s old Albert Hall Cream sparring partner, Jack Bruce.

Watching the movie or listening to the album now is to grasp the full flavor of an outfit instinctively attuned to travel in any direction Gallagher fancied… be it the meanest, dirtiest blues or expansive exploratory Celtic modal tunings.

“It was what was going on. From ’71 ti ’74 we were touring the states almost non-stop. That really tightens you up as a band,” McAvoy recalls. “You’re going out there playing clubs and arenas with the Faces and Deep Purple, but after your gig you’d go down to a club and hear more great musicians.

“In Chicago we all went down to see Otis Rush, then we saw Willie Dixon playing one night. You’re looking at the music that made you want to play in the first place… in the city where it was born. How could it not affect you?

“We’d go and see these fantastic musicians who were inspirational to us. The next night you go on stage and you wanted to be like these guys.

“We were getting tighter and tighter and tighter.”

Two years after Irish Tour ’74 was filmed, my father took me to see a Chuck Berry concert at Belfast’s ABC cinema, where a periodic security forces-imposed curfew, and higher than usual ticket price, helped account for the meagre crowd. It was amazing to see Chuck Berry but the lifelessness of the atmosphere was completely at odds with the fearless fascination and community unifying glee I experienced when, unchaperoned, I went to see Gallaghe at the Ulster Hall in the same year.

Growing up outside Belfast, the city had become a place of considerable foreboding to me. But the elation experience in the Ulster Hall was something else. Gone were the horrors of sectarian conflict, the pure sense of feeling, of basking in — and being part of — greatness captured on film in Irish Tour was , in the flesh, magnified, many times over.

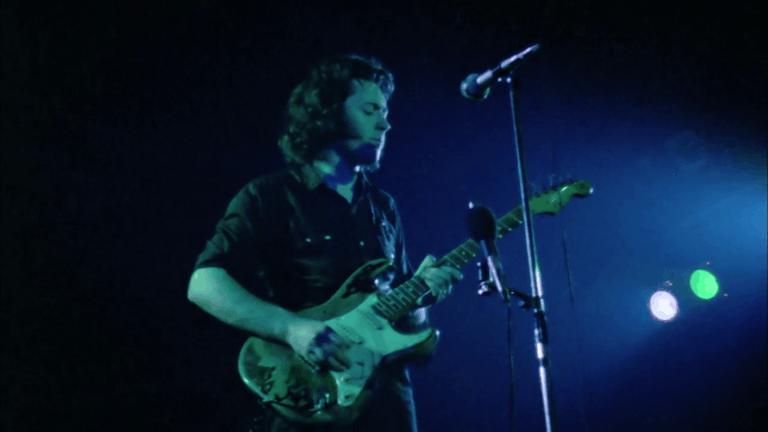

Screen shot from Irish Tour documentary

There was nothing more I’d ever really want — or could ask for — from music than the sense of purpose and righteousness that night in Belfast offered.

While Ulster, as ever, teetered towards the brink, inside The Ulster Hall, Rory’s rock hit with righteous affirmation. The effect I felt would be widespread. The same night I saw Gallagher, a young kid by the name of Joby Fox, let into the venue as the show climaxed by a kindly doorman, also felt the transformative power and embarked on a life of music making.

Thirty-six years later, Fox is still a professional musician based in the city and, in wisecracking Belfast style, remembers the evening as “fitful”.

Gallagher easily bridged tribal divides, inspiring regular Ulster Hall attendee Jake Burns, later front man of Belfast’s premier punk band Stiff Little Fingers, to pick up the guitar. Gallagher would later guest on albums by SLF and Fox’s former band, Energy Orchard. It is understandable that his reputation has increased since his death, so profound was the effect he had during his lifetime, not just in Belfast but all over the planet.

As a film buff and a perfectionist who fun it hard to cede control to outside forces, whether manager, director or producer, Gallagher was an inevitable presence in the editing suite when the time came for Palmer to cut the movie.

“He was fascinated at how the editing worked. At that time we were using celluloid and kept saying, ‘So it’s all held together with Sellotape?’

“He’d seen the Cream film, 200 Motels (Palmer’s Frank Zappa movie) and All My Loving.

“What he didn’t want was a straight concert picture like the Cream film, which I didn’t want to do either. It would have been too much like hard work.

“He just wanted a film that demonstrated his skills but he wanted to know how we could make it different.

“I said to him, ‘Rory what is different about it is you. You ain’t Mick Jagger… and thank God for that.

“You ain’t as stripy as my friend Lennon. Thank God for that. You are you. And this film is all about capturing you.’

“One thing he was worried about was filming in the dressing room because, he said, ‘nothing ever happens’.

“I said — exactly! On stage you’re all up and at ’em — backstage you’re trying to find some way to open a bottle of Guinness, tuning your guitar, looking knackered.

“He was quite happy to have it done but didn’t see the point of it until he saw it put together and then he realized. What it showed was a working practical musician who was just like you and me.

“Only he could play the guitar off the fucking planet.”

And, of course, it was that ability and its concomitant effects that Palmer captures most vividly in the film.

“Rory had two incredible qualities — he could play like nobody else, and somehow his personality was something the audience responded to in quite a loving and open way.

“They thought he was on their side. It’s one of those indefinable things you immediately sense — if a performer is on your side or in your face — they just knew he was one of them.

“The other thing is that there was absolutely no bullshit about him, it wasn’t that he was rude but he wasn’t there to talk to the audience. You didn’t want to hear, and you didn’t get, funny stories from him or the history of the universe or the meaning of life. Audiences respect that because they get fed up with people yakking at them.

“The real feeling at the end of every concert was an absolute joy of music, making real uplifting joy. It just lifted your spirits. You felt completely elevated by it.

“It’s not for me to say if I succeeded or not but that was certainly the quality I tried to get across.”

Palmer’s approach to filming Gallagher was markedly different to the method he’d deployed with Cream.

“We only had one camera. That confused Rory quite a bit. At the Cream concert we had four colour video cameras, but they were so clumsy and difficult to move. One of the problems was that I had given each of them their own camera and said, ‘Eric, please don’t turn your back, I can’t move the camera if you do’, and of course he did, not on purpose, it was just what he did.

“With Rory in concert I wanted it to feel as if you were actually there. We could film the same number in four different venues. I said to Rory, ‘As long as you don’t change your shirt it will be okay.’

“He said, ‘but it will be very smelly’.

“I said, ‘Don’t worry, you can’t smell on film,’ and for the most part he kept the same shirt on.

“What I was trying to do was make it as fresh as I could, which meant long takes — not lots of cuts, swooping over the audience and all the rubbish you see now.

“I wanted to shoot it up close and personal, so that the viewer would feel what I was feeling, sat on stage.

“That intrigued Rory. After the Belfast concert we had a discussion and he said, ‘I didn’t notice until after 10 minutes where you were’.

I said, ‘I was right alongside you on stage’. He said he’d realized but it han’t worried or affected him at all, once he was aware.

“You can’t take that awareness away but it han’t affect his performance.”

As a display of guitar rock theatrics and dynamics, there is no greater teacher for an aspiring guitarist than Gallagher. The unbridled emotion captured in the heat of performance on Irish Tour ’74 remains eternally inspiring.

“What young guitarists — or anyone watching the film today — can take away is the joy of making music for its own sake.

“There’s an audience reacting volubly but, this isn’t a show in the putting on a performance sense, the players are focused on each other, listening to each other, making music because it’s a wonderful thing to do,” says Palmer.

Irish Tour captures the dichotomy of Rory Gallagher, too. Away from the crowds, the on stage avenger in full valiant flight, galvanizing the feeling of fresh excitement and “open, loving” quality Palmer felt, becomes a lone meditative figure, keeping his own thoughts and counsel.

“This was a shy man who was cast into a spotlight he didn’t exactly feel comfortable with. He knew it was his destiny– but it didn’t make it any easier for him to accept.

“I think loner is too strong a word but he was, like all great musicians, like all great artists. they are on their own and they know that is part of the price they pay to do what they do.”

Ten years after Irish Tour, in the summer of 1984, Gallagher’s second Belfast performance on his first Irish tour in four years coincided with six IRA bomb blast across the city. Economic depression and a heroin epidemic now added to the cruel divisions wrought by violent sectarianism. Creem magazine writer Bill Holdship found a still music-starved country being given sustenance by the ever-faithful returning here.

Rory Gallagher at the Ulster Hall in 1984, photo provided by Stephen Loughins

“He’s a national hero here because he’s out there playing for the farmers and people who don’t normally get to hear live rock music,” road manger Phil O’Donnell told Holdship, as the tour headed out from Belfast to more obscure and forsaken rural outposts.

Gallagher was in good spirits, with The Clash and Elvis Costello among his muddy Waters and Bo Diddley tapes, forwarding the tantalizing idea that Dylan (a professed Rory fan) should record a Highway’61 for the 1980s — offering himself up to play the Mike Bloomfield role.

As approachable as ever to fans, Gallagher was the primal warrior at pains to stress the need for the music that had propelled him to be sustained, unimpressed by the newly fashionable wave for synthesizing music and feeling.

“I don’t believe in computer glorification or the electronic age because, in the end, it’s going to be our source of destruction,” he told Holdship. “The press about what’s going on over here has frightened people and I suppose, if I were English or American, I’d think twice about coming here.

“The sad fact is there a new rock fans growing up and they need to hear live stuff. So I suppose you could call it a service in a very small way, but I feel it’s the least you can do if you grew up playing in these areas and you have a sort of following here.”

Two years before the guitarist died, Palmer once again met up with Gallagher with a view to shooting a follow-up documentary.

“He wasn’t very well but playing again, trying to put Humpty Dumpty together.

“It was very much along the lines of ‘The last film was such fun, let’s do it again’. I said, ‘Of course, but there’s only one problem. I haven’t made a rock film since 1976 and I didn’t want to make any more, but you will be the exception.

“He laughed and thought that was very funny but the idea never got anywhere.”

McAvoy’s last contact with Gallagher, a Christmas phone call a year after he left the band, was strained. Gallahger wasn’t in great shape. At what would be his last London show the same year, visibly the worse for wear, he was taken off stage by his brother Donal.

“It’s a shame the audience didn’t realize the pain he was going through,” says McAvoy. “But maybe he shouldn’t have been on stage in the first place, although that’s easy to say in retrospect.”

Palmer adds: “Since he died, Rory’s reputation has gone up by leaps and bounds — and thank God for that.

“It went through a terrible slump and decline, partly thorough his own making, in the 80s.

“His moment in the sunshine was the few years before we made the film and the three or four years that followed.

Rory Gallagher Band June 1972-May 1978

“He did his best to keep his feet on the ground but sometimes it gets to you and it got to him. I think he felt quite depressed about it. In the end it takes you away from the thing you know you should be doing — playing the guitar. Once the record company and PR mating gets going you are on the road to nowhere. I don’t think he got the support he needed.

“When De’Ath left that was trouble for him. There were antagonisms in the group. There always are but they were his family. That was true for a lot of bands but it was particularly true of Rory. I witnessed some pretty cross scenes between him and Gerry McAvoy, but in the end they had a bond which was, ‘We’ve got to get out there and play like hell’. the were bonded together, no question of that. When your family fractures it can leave you not knowing what to do. I think that left him lonely, and loneliness brings other things along. In Rory’s case, I thin that was drink.”

But Rory’s great work — and there’s a wealth of it on Eagle Rock DVD, the Donal-curated album reissues and YouTube — endures, laying down a challenge and inspiration to future generations. Surprisingly, in today’s new-fangled history celebrating Ulster Hall, the pivotal importance of Gallagher’s remarkable run of shows there is underplayed. There’s a plaque, but more fashionable UK names played there get prominence. A shame. At least in Ballyshannon they have a statue to celebrate his memory.

But Gallagher was only in Ballyshannon for a few months at the start of his life. It was within the walls of the venue on ‘bomb alley’ that the tender-hearted, soft-spoken, dogged determination and captivating presence of Ireland’s guitar warrior poet and people’s hero found its fullest flowering.

Gavin Martin, The Blues Magazine, Nov 2012

Share on Facebook