Jul 13 2012

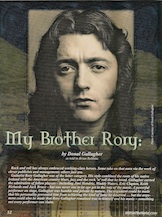

My Brother Rory: by Donal Gallagher — as told to Brian Robbins

The following is Part One of Brian Robbins conversation with Donal Gallagher published in the 20th Anniversary Issue of the music magazine Hittin’ the Note. Many thanks to John Lynskey, publisher of Hittin’ the Note, and Brian Robbins, the author of the article for allowing me to post this to my blog. Part Two of the interview is in the latest issue of the magazine and will be posted here soon. For those that can’t wait you can order the latest issue of the publication through their online presence at: HittintheNote.com. And be sure to catch Brian’s previous reviews of the new album Notes from San Francisco, the re-release of Rory Gallagher’s classic albums, and the Blu-ray DVD of Irish Tour ’74 on jambands.com.

My Brother Rory — Part One

Rock and roll has always embraced working-class heroes. Some take on that aura via the work of clever publicists and management, others just are.

Guitarist Rory Gallagher was of the latter category. His style combined the roots of his native Ireland with the American country blues, jazz and the rock ‘n’ roll that he loved. Gallagher earned the admiration of fellow players – including Jimi Hendrix, Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Jack Bruce – but was never one to let ego get in the way of the music. A powerful performer on stage, Gallagher was humble and private by nature. The argument could be made that his personality prevented him from achieving the kind of fame he deserved … but the argument could also be made that Rory Gallagher remained true to himself and his music – something not every performer can claim.

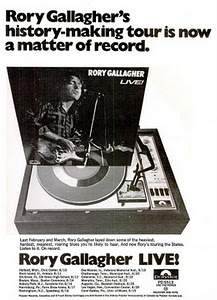

Rory Gallagher died in June 1995 at the age of 47 from complications following a liver transplant. The music he left behind will forever be fodder for “how did he do that?” discussions in guitar circles, and still continues to attract new fans. 2011 saw the re-release of Gallagher’s catalogue of classic albums (both studio and live) by Eagle Rock Entertainment, along with some great live performances on DVD and Blu-ray. Newly re-mastered (and including some previously-unreleased material), this new wave of music has something for both the uninitiated and the longtime Rory fan.

Rory’s brother Donal oversaw the re-release project, his duties carried out both as family and from the viewpoint of having been there himself. Throughout Rory’s career, Donal was by his side as his “road manager,” a title that hardly does his role justice. Perhaps “brother” is truly the best title of all.

Donal Gallagher was kind enough to share some of his memories of Rory with Hittin’ the Note. Granted, his stories could fill a book (and possibly will some day), but in the meantime, we’ll need to be content with just a few glimpses into the lives of Rory and Donal Gallagher.

One of Donal’s earliest musical memories of his brother is of a young Rory listening to American Armed Forces Network radio, broadcast from the Navy base in Derry, Northern Ireland during the Cold War:

Rory always had this kind of amazing understanding of music. It wasn’t so much the blues at that time as it was jazz – The Voice of America Jazz Hour on the radio. He must have got the gene from my father, in terms of the ability to play and instrument.

I remember Rory’s wish was to get a guitar – and at that time, a guitar wasn’t a very common thing. I recall trying to make guitars and banjos from round Kraft Cheese packets, rulers and elastic bands. Rory had just an unnatural appetite to learn all about the musicians and the music.

After the jazz guys came the blues guys: you had a lot of American influence from the musicians who’d come over to England and stayed on. Chris Barber is someone who doesn’t get his full credit – a traveling jazz/blues bandleader who had a show on the BBC radio. He brought people like Muddy Waters and Albert King to Britain. Hearing them on the radio was Rory’s musical education.

Donal described how early “musical differences” between he and Rory set the stage for his career as his brother’s road manager:

Rory, being the older brother, was always right, of course! But in fairness to Rory, he always had this tuned-in direction for himself. He knew where he was going, what he wanted and didn’t want – and was very clear about it. We were always close; the family had a lot of movement from city to city as we were growing up. Our father’s family lived in Derry in Northern Ireland, while our mother’s family lived in Cork in the south – very different feel and identity.

As Rory developed his guitar skills, he played at hospitals and at church concerts. I was brought in for harmonies: we thought ourselves the Irish version of the Everly Brothers – at the age of, oh, nine and eleven! One night I tried to fill out the time with a traditional Scottish piece I knew, but stopped a ways into it to tell Rory that he wasn’t playing it right – he was trying to put a rock ‘n’ roll feel to it.

I guess I embarrassed Rory – I got “fired” that night! I ended up doing whatever I had to do to get back in his good graces, including carrying his guitar and amplifier. That’s when I became his “roadie.”

Rory wasn’t going to let the violence stop him from playing to people

We’ll fast-forward now to one of the highlights of the new Eagle Rock re-releases, the Irish Tour ’74 album and video, featuring Rory, drummer Rod De’Ath, bassist Gerry McAvoy, and keyboardist Lou Martin. The period was an especially troubled one in the country’s history, with violent clashes between the Protestant unionist and Catholic nationalist communities in Northern Ireland. Nonetheless, Rory Gallagher wanted to take his music to everyone.

It was certainly dangerous to be on the road in Ireland in 1974 – particularly Belfast. The venue where the Irish Tour ’74 concert was filmed was the Ulster Hall there. The street it was on got renamed “Bomb Alley.” Just to give you an idea of things. You couldn’t predict anything as far as the bombings went… there was no protocol to it. It could happen anywhere. One of the hotels we stayed at was demolished by a bomb just after we’d moved on.

I remember playing on New Year’s Eve when eleven bombs went off in the vicinity. And we were all waiting for the twelfth one. When we said anything about it, we were told, “Apparently they’re saving the big one for next year.”

We were warned not to drive overnight, as well – to do all our traveling during the day. But we figured, “if we drive overnight, we’ll make better time.” And Rory wasn’t going to let the violence stop him from playing to people.

Recorded four years into Rory’s career as a solo artist after the breakup of the power trio Taste, Irish Tour ’74 is a snapshot of the quartet at the height of its powers. A sweat-soaked Gallagher brandishes his beloved battered Strat for much of the performance, leading his band mates to places far beyond the walls of the Ulster Hall.

In the beginning, that was meant to be a documentary about Rory and Ireland for the BBC. Rory said, “With this band and this lineup, I just want to get it recorded – it can’t get much better.” You know, he had a sense of it: the simplicity, the dynamics, the kind of psychic thing that was going on between the guys at that point. There was never a set list; there were a lot of nights that he might open with the same number, but it was so unpredictable that the guys would say to me, “Do you know what Rory’s going to open with?” And I’d have to tell them I had no idea.

There was this feeling of keeping it on the edge and unpredictable all the time. they’d take a song somewhere and you’d be watching, think, “God, they’ve really gone out on a limb … how’s he going to get back into the main part of the song?” And somehow they’d manage to bring it back in. At the end of the day, you have to please yourself on stage and that’s what they did every night. There was an excitement – like a football final or something. Whether there was 100 or 100,000 people in front of him, Rory played to them, brought them in with that electricity. Their vibes would come into it and he’d play off that, as well. They performed their part. Everybody was involved.

As mentioned earlier, Rory Gallagher’s talent was well-recognized by his fellow musicians – including the Rolling Stones, who had their road manager make a call to Ireland after Mick Taylor’s departure from the band in December 1974.

After Rory delivered the Irish Tour ’74 record to Polydor – that was the final album of a six-album contract he had with them – Rory was in a position to do whatever he wished.

It was the early days of January ’75 and we’d just gotten back home and had one or two days off. As I remember, it was around midnight when the phone rang. I knew it was long distance as in those days you had to connect to an operator to call another country. Of course, whenever you got a call that late at night, you’re worried that someone’s been killed in an accident or something, you know?

This guy comes on the line and says, “Have I got the right number for Rory Gallagher?” in a very British accent. This was at the height of the troubles, of course, and it had been suggested to me that Rory was a possible kidnap target.

I’m being very evasive about whether he had the right Number or not, trying to find out who he is. I finally said I could get a hold of Rory, but it would take a few minutes – could I tell him who’s calling? And the guy said, “My name is Ian Stewart.”

Of course, speculation was rife at that time about who the Stones would have and immediately I put two and two together. I almost blew it by saying, “Of the Rolling Stones?” – but I held back and said, “Of … London?”

I told him to hang on, as I could get Rory, but it would take a few minutes. Rory had gone to bed a short while earlier, so I knocked on his door and said, “You’ve got a phone call downstairs.” He said, “Who is it?” and I said, “It’s the Stones.”

Of course, he thought I was having a prank with him and refused to get up. Eventually, though, he went down and took the phone call. They wanted to know if he could be in Holland on the tenth of January – was he willing to come over and have a jam with them? Rory said he’d be delighted and honored.

We then returned to London immediately – there was a tour booked for Rory at the end of January in Tokyo. When the ticket to Rotterdam showed up, there was only one, “Where’s mine?” I asked. Rory said, “There’s only one – I guess you’re not coming.” He was really thinking there was no need of me being there while they were just sitting around and playing, you see.

The simple fact about it was that Rory was the one the Rolling Stones wanted; there was no one else in the race at that time. If you think about the music the Stones had been releasing in the years prior to then, the Mick Taylor years were really a golden period. They were trying to find someone who could fill that gap or even embellish that scenario. Rory was the closest person to fit in that role.

When the Stones started their own label in the early ’70’s, Keith Richards mentioned in interviews that one of the artists they’d like to have was Rory. He’d obviously listened to Rory and recognized how he had combined some variation of American country music – which Keith loved – into rock and roll. Of course, the Stones are always referred to as “Keith’s band,” but Mick Jagger really runs things as far as the financial arrangements and “who’s in/who’s out.”

In the meantime, the Stones postponed the date they wanted Rory to come – and we were close to the start of the Japanese tour. They told us that the Stones mobile recording unit was having problems and they needed to get it going. But I think what was really happening was Keith was going through one of his worst drug periods. When Rory finally got the call to come, he took his Strat and a small Fender Champ amp and flew across to Holland on his own.

On the night of his arrival, Rory was met at the airport by Mick Jagger himself. I remember Rory telling me it was snowing and he was standing outside freezing with his guitar and amp while Mick went down the taxi line negotiating the rate to Rotterdam. There were no stretch limos!

Marshall Chess Jr. was managing the Stones at that time. Rory allowed that when he and Mick got to the concert hall in Rotterdam where everyone was waiting, Marshall said to him, “Welcome to the Rolling Stones. You’re the guy for the job and I’m delighted that you’ve come and joined us.”

Rory didn’t know what to say, of course. And when Marshall asked him, “Who do I talk to – where’s your management?” Rory had to tell him, “Well … he’s not here. I … I just thought I was coming for a jam.”

They got a session going that first night, but Keith didn’t turn up for it. Mick was nervous; that’s when Rory realized Mick and Keith weren’t on talking terms and Mick was trying really hard to get the band back together. Charlie and Bill had no say whatsoever, so they just stayed out of it and just came in when they were recording. Mick says to Rory, “Look, I’m not sure about Keith – whether he’s going to come down or not. I’ve got a song I’ve been working on … have you got a riff for me?” Rory had been writing a song and he started up a riff. They began making music; started getting down to work. I think the song was “Hot Stuff.”

The next evening, Keith showed up. Rory told me they did four tracks, one of them being “Miss You.” I believe I know when Rory heard that track later on he said, “That’s my riff.”

Finally it got to the point where Rory had to say to Mick, “Look, I need to be in Tokyo in a few days time – I’ve got a tour. What’s the plan here?” And Mick said, “You’ve got to have a conversation with Keith. He’s waiting up in his room for you, go up and talk with him.”

So Rory goes up to Keith’s palatial suite and finds the door wide open. Rory walks in to find Keith on the bed, completely comatose. Rory stayed up all that night, checking every half hour to see if Keith was up or if he could wake him gently, but he was too out of it. By eight o’clock the next morning, Rory – who hadn’t slept at all the night before – packed up his guitar and amp, got on the plane and flew back from Rotterdam to London. I met Rory with a fresh suitcase at Heathrow and we flew straight to Tokyo.

There was really very little conversation between us about what happened in Holland with the Stones. I think Rory’s attitude was, “If they wanted me badly enough, they would have told me.”

Upon reflection, if I’d been there… I don’t know how it would have worked out if things had been different. It’s one of those ‘what if’ things.”

This concludes part one of Hittin’ the Notes’ visit with Donal Gallagher. The second half of the conversation with Donal is in the current issue of Hittin’ the Notes and includes memories of the sessions behind Rory’s newly-released Notes From San Francisco album. Stay tuned for the second half of My Brother Rory…

Share on Facebook