Mar 23 2012

Rory Gallagher: Live at the Bridge House!

Every town’s got one. Call it a pub, a bar, a roadhouse, a juke joint, every town has a place where live entertainment rules. A place where the locals come to hear the best bands, where the up and coming musicians hone their skills, develop a fanbase, and hopefully one day land a record deal. It is a place where established musicians come to jam away the hours between tours. Where the crowds cheer on their favourite bands and Proprietors take care of them like they were family. For the London Burrough of Newham, that place was The Bridge House in Canning Town. Named after the old Iron Bridge that spanned the River Lea, the Bridge House became legendary for who played there, the list as long as your arm … and then some.

From 1975 to 1982, the Bridge House, Canning Town, in the East End of London, was the place to be. Heavy metal fans rubbed shoulders with punks, mods, skinheads and goths to watch Iron Maiden, the Tom Robinson Band, Secret Affair, Cockney Rejects and Wasted Youth. The 560-capacity pub is where Dire Straits, U2 and the Stray Cats played their first UK dates, where The Blues Band and Chas & Dave recorded live albums, and where Depeche Mode got signed.–Pierre Perrone, The Independent

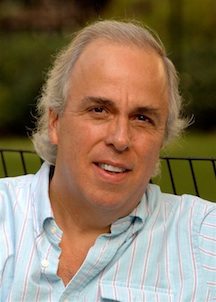

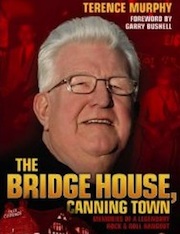

The proprietor of the Bridge House was a local boxer named Terence Murphy, who had previously run the pub, Rose of Denmark, and then the White Hart before taking over the Bridge House. It was Terry who made the Bridge House into the legend it became. “From Depeche Mode to Dire Straits, from U2 to Chas & Dave, so many music acts that were destined for huge success performed their first gigs at this unassuming and unique place.” In 2007 Terry wrote a book chronicling those times between 1975 and 1982 when he ran the legendary pub. One of the highlights of his time as proprietor of the Bridge House was meeting Irish legend, Rory Gallagher, and in the book he talks about Rory coming down to the Bridge House to jam. The following is an excerpt from his book, The Bridge House, Canning Town — Memories of a Legendary Rock & Roll Hangout. Special thanks to Terry for allowing me to post this on my site.

The Bridge House, Canning Town — Memories of a Legendary Rock & Roll Hangout

RORY GALLAGHER (pp 57 – 63)

When Rory got to hear about us, down he came, but he kept us waiting. ‘Is he or isn’t he going to do a song?’ The last song of the night, up he went, and never came off the stage for two hours, continuing until 1am; and we were meant to close at 11pm! But Rory overruled any laws; if the police had come in, I don’t think they could have stopped him. He was so good, they wouldn’t have wanted to anyway.

Before their next tour, in 1981, Rory Gallagher and his band appeared on stage Live at the Bridge; what a great night! Rory’s brother Donal, his manager, allowed us to advertise the gig and before 8pm the pub was packed with fans from all over Britain and Europe. Donal made a video of the gig at the Bridge. I wonder if he has still got a copy of it. I must try to contact him, as I would love to see it. [*milo: Unfortunately the video along with other memorabilia was stolen from the Gallagher residence years later]

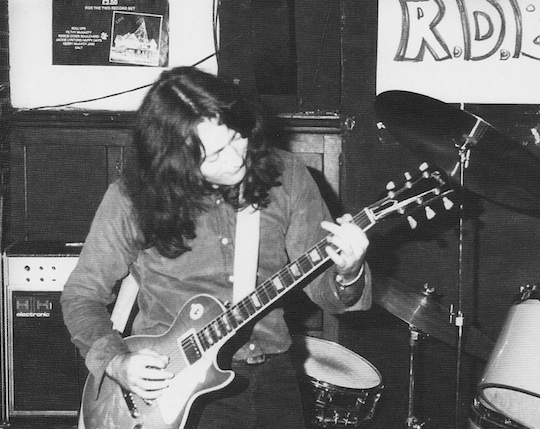

Rory at the Bridge House

Rory was born in Ballyshannon in Donegal in 1948, but lived in Cork where his family had a pub. Rory loved it there. Here we had the ordinary fellow at home not the Rock star he was in all parts of the rest of the world. Well, that was his feeling, but to the community, while at home, people would just stand and watch every move he made. There is no other expression for it but ‘hero worship’. In his adopted home town, he was a king.

When he was 15, he left home and joined a show band. He later lived in Belfast where he formed a new band, and so as not to leave a bad taste he called the band Taste. This was the band my good friend Gerry McAvoy was to join. Another friend who was in Taste was Wilgar Campbell, who played drums. [*milo: Terry is actually referring to the first lineup of the Rory Gallagher band with Gerry McAvoy and Wilgar Campbell] …[Wilgar] would later form his own band and play at the Bridge House in a three-piece with Gary Fletcher (guitar) and Dave Kelly as front man, when not working with Paul Jones in his Blues Band.

After Gerry McAvoy introduced me to Rory at the Bridge House, we became good friends. He invited me to all his gigs and I went to most of them, being offered the VIP treatment, with limos, backstage passes, etc. I even got to ride in his helicopter when we got lost at the Gallagher Macroom Festival in Cork.

Rory at the Bridge House

The Macroom Festival was the very first open-air Rock gig in Ireland. It was held in the grounds of Macroom Castle in the summer of 1977 and what a day/night and day it was.

Gerry and Top Driscoll had popped into the Bridge House for a quiet pint before going on their travels. Gerry had said, ‘You’ve got to come to the festival. Rory would love to see you.’

‘Great!’ I replied. ‘Where is it? Hammersmith Odeon?’

Gerry in his soft Irish voice answered my question saying, ‘Aw, no, no. It’s at Macroom.’

‘Is that outside London?’ I asked.

‘Just a little,’ said Gerry.

Tom cut in: ‘Jesus! It’s in Cork, in southern Ireland!’

We all had a drink and I asked my son Lloyd, who was serving us, ‘ Do you fancy going to Ireland to see Gerry and Rory play?’

I knew he was a big fan of their music so he jumped at the chance. Gerry gave me his hotel number and told me to ring him once we got to Cork.

We arrived in Cork the day before the gig and booked a nice room in a hotel. We met up with Gerry in his hotel and went straight to the bar. The Murphy’s stout was going down a treat so we had a very pleasant evening.

The next morning, we had a tour of Cork in the limo that Rory provided for us. Then we went off to the gig. These cars had special passes to get into the backstage car park, which was kept a secret. The route had been made known only to promoters, the artists and management. If the fans had found out, we wouldn’t have been able to get through the crowds. I believe there was something like 50,000 fans, so there had to be a clandestine entrance.

When we arrived, we went straight to the band’s dressing room. Gerry, Rod De’Ath and Lou Martin were waiting there. Gerry said that Rory would like to see me, and he took me into Rory’s dressing room. Rory was all alone and, when I went in, Gerry left. This surprised me, but this was Rory, a quiet unassuming man, completely different from other Rock stars I have met.

He gave me a drink, I thanked him and said, ‘God bless you, Rory.’

He looked me right in the eye and asked, ‘Do you mean that?’

‘Of course I do!’

‘Let’s prove it.’

So we sat down. I looked at him and said the Lord’s Prayer. After I had finished, he smiled and said, ‘And god bless you, Terry Murphy.’

He asked me where my ancestors had come from and I told him Cork. ‘Ay,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘that’s the reason; we may be related.’

I don’t know what the reason was, I never asked, but it did seem as if he had been thinking about me. Perhaps being older than him, I was the father figure he was looking for.

Gerry came back, so we wished them all good luck and said we would see them after the gig.

There was a special place set up in front of the stage for the guests of the artists. There were other great bands on the show including Status Quo. But everyone was waiting for Rory. Earlier, back in his adopted home town, the crowds had gathered to watch and cheer as he arrived in his helicopter.

Quo at last finished their set. Now, they awaited their ‘god of Rock’ to arrive on stage.

We watched as Tom Driscoll did all the last-minute checks to the onstage equipment. He winked and raised his splayed right hand; five more minutes to wait. The DJ finished his last record and it went deathly quiet. Then there was a screeching of car tyres and seconds later Rory ran on stage.

‘Welcome, Mr. Rory Gallagher,’ shouted the announcer, but nobody heard it.

Rory went straight into ‘Bullfrog Blues’, the perfect start. The gig just went into full throttle, getting better and better, and the fans were going mad.

Standing in front of us was one Johnny Rotten aka John Lydon (of Sex Pistols fame0, along with Bob Geldof of the Boomtown Rats and a publicist I was to meet later, as well as a few other friends of theirs. Lydon had come in with this bucket of urine, and his friend had another one, and they threw it at the band. Me and Lloyd rushed over to stop the second bucket being thrown. The security was quickly there and they were thrown out. Yes, Sir Bob included! Rory was raving, although none of the urine reached him. If it had gone on his guitar or the amps they could have been electrocuted or set alight.

There was a reception after the gig and the newly formed Hot Press was handing out awards to the bands. It was a nice reception. Gerry, Lloyd and me were standing at the bar, when who walks in but Johnny Rotten. As he came bowling up to the bar, Gerry, remembering the earlier incident, said, ‘I’m going to kill him.’

Gerry threw the best right-hander he had ever thrown, but Lloyd blocked it and I grabbed Gerry. I told him, ‘That’s what he wants, cheap publicity. Don’t let it show.’

By this time, Rotten had run away. This whole incident was filmed by a German film crew, and Gerry has a copy of it, which will be nice to see one day.

Gerry’s management had come to his aid and ushered them all out the door, and then they were gone. There was em and Lloyd left in the hall with no idea where the band were. They had left the hotel where they were staying and there was another reception that we had all been invited to.

While we were standing there wondering what to do, an official came over and told me that Rory was on the phone. He told me not to worry and that he would send someone down to pick us up in about half and hour. We waited for well over an hour, and then all of a sudden there was a terrible loud noise over the hall. What a surprise! Rory had sent a helicopter to pick us up and take us the 10 miles back to Cork. A lovely time was had by all.

Gerry and Tom came back to London with us and who’s sitting next to us on the plane? Bob Geldof. During the flight, we downed a couple of bottles of champagne and Tom looked like he was going to give Bob a wallop.. A good job my son Lloyd was there to stop him. We managed to get to London without any serious incident and I dropped Tom off at his home before we hurried back to the Bridge House where we had a busy gig to promote.

We were to see a lot more of Rory, Gerry, Rod and Lou as they continued to play for us at the Bridge. Rory was to change his drummer on a couple of occasions, first to Ted McKenna and then Brendan O’Neill; they both became regulars at the Bridge, thanks to Gerry McAvoy.

Gerry and Brendan now play with another band that started at the Bridge, Nine Below Zero. They had started with us as the Stan Smith Blues Band, and their harp player, Mark Feltham, had joined Rory’s band with Gerry and Brendan. Now they’re altogether in this band fronted by founder member Dennis Greaves on vocals and doing very well indeed as one of the busiest bands on the circuit.

The last time I saw Rory was down the Kings Road, Fulham, in 1994. My daughter Vanessa had put on a musical play down there. Rory, seeing the name Murphy on the promotional material, had come down to support us. He was living locally and he looked fine. It was a lovely to see him. He didn’t stay to see the musical but we had a drink together. I remember saying to him, ‘See you at the next gig,’ and he replied, ‘I will not be playing any more.’

I turned to him and said, ‘What about Gerry and the guys?’

He looked me in the eye, and his eyes were sad as he said, ‘Oh, they’ve got a new band together. They’re looking after themselves.’

This was not the Rory I knew. He had put on a bit of weight, which all musos do when they’re not on the road, and he seemed very sad. Little did I know that at that time his liver had packed up and he was waiting for a transplant. Sadly, he died on the operating table at the age of 47. It was a really big loss to the whole world.

On the day of Rory’s funeral, the hearse left O’Conner’s Funeral Parlour with Rory’s Stratocaster guitar laid alongside the coffin. Crowds of people lined the streets, and traffic was at a standstill. Nobody cared; they were all in dee mourning. As the hearse pulled up at the church, the rear door was opened so Donal could lift the Strat away from the coffin. He handed it to Tom O’Driscoll, who had been with Rory for 18 years. As Tom took the guitar, his eyes met Donal’s. It was the very same action as when Rory left the stage, always handing the Stratocaster to Tom. The tears were never far away.

Then a strange thing happened. The very quiet deep-in-sympathy crowd began to cheer and applaud, a very rare occurrence at a funeral. This showed us that this was not just an ordinary funeral..We had come to bury Rory Gallagher, our god of Rock. Everyone was pleased. Donal glanced at his wife, Cecelia, and his children and at last there was a smile in his eyes instead of the tears of the last week. Even the sun shone brighter at that moment. Was that the moment Rory was passing through the gates of heaven? We like to think so.

You can purchase the book The Bridge House, Canning Town — Memories of a Legendary Rock & Roll Hangout as well as various CD’s of the Bridge House legends at the Bridgehouse’s official online shop, here: Bridge House Online Shop. Thanks again to Terry Murphy for allowing me to reprint this excerpt from his book, and for the photos of Rory playing at the Bridge House. More photos of Rory at the Bridge House can be seen on Chino’s Forum.

Share on Facebook