This poem is not meant to be an accurate depiction of the life and times of Rory Gallagher but more a fantastical take on his life with a bunch of what ifs and what mights. Apologies to those easily offended, or expecting a better poem.

Return of the King

Amidst the swell and savage pull of a black-faced Irish Sea

A rusted ship like pocked cork bobs and seeks out the river Lee.

Coming home at last from London town with sad and heavy freight

Returns half mast with native son, the last of the Irish Kings.

A Donegal lad, an Irish minstrel who plied his trade abroad,

Yet come every year to Belfast he did duckwalking the halls of Ulster.

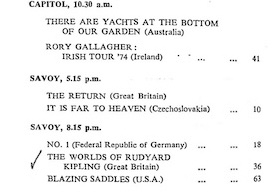

No more will he tread the boards of Tralee, the Carlton, the Savoy or Stadium,

No great flying leaps or machine gun assaults, the stage is now left abandoned.

On comes the heavy laden ship, with grey and rust-stained keel,

It’s cargo holds no Pharaoh cold, no lords from Whitehall leap.

No glimmer twin in fancy raiment, no star from cine reel,

Just prodigal son in denim and Strat now returned to his Irish keep.

Swansea – Cork Ferry

Below the decks two figures sit, true brothers in all but name,

Between them lies the iconic Strat, the Bluesman’s diadem.

A survivor of countless roads less traveled, blood ’n sweat infused in its grain,

Still waits for the hands, the lovers caress, fleet fingers in wild abandon.

No more will it sing or cry out in pain, no sharp agony of notes,

The master’s hand now laid to rest, the strings forever mute.

What stories it could tell of life on the road, the nights so filled with music,

The roar of the crowd, the stamping of feet and “Let’s have another one Rory!”

And sure enough one more would be sung again and again and again,

Until lights would go on and the crowds stumble home with looks of exultant glory.

But long years had passed since his days in the sun, his hold on fame fast fleeting,

The crowds had thinned out, and left him to doubt his God given ability.

His life on the road had taken its toll, his body could no longer withstand

The soaring high leaps, the Chuck Berry duck walks that once was a part ingrained.

A lonely sad soul with a heart of pure gold, Blues fire still burns from within

As he played his guitar in smoke-filled bars, squeezing notes in the rumble and din.

There came such a time he could no longer go on, his body now sick and weak,

He collapsed on the stage, stunned silence gave way to boos without surcease.

The end of his days were in hospital stays, no medicines could cure body or soul

From long years on the road, the pills, alcohol, and the heartache of a man forgot.

The ship steams west to lay his body to rest in fields of Irish clover,

His brother and Tom, long journeymen bound, replaying long nights forever.

A naked bulb swings from the ship’s high beam, shadows play across their visage,

Transfixed in their grief their counsels they keep and bear witness to this final voyage.

The ship arrives at dock Leeside, black night replaced with grey.

Coiled ropes are hurled from arms inured, a thousand orders belayed.

From within the ships great cargo hold, the precious freight emerging,

Plucked up by crane, shuttled across ship’s main to stevedores awaiting.

No fanfare awaits the return of the king, no trumpet blasts ensue;

No milling throng, or staid Lord Mayor to mark the solemn milieu.

Shandon Bells

The Bells of Shandon at the church of St. Annes tolls by the waters Lee

And startles a gull that’s perched on the hull of the ship now docked on the quay.

It takes to the air with a squawk and a glare, away from the din retreating

And streaks to the west as if messenger sent to announce the return of the king.

Soaring on thermals, it banks to Cork central, down to MacCurtain Street

Where the once-favored son called a lively pub home by the banks of the river Lee.

What tales could be told in those Crean-coloured walls high above the once Kingly street,

Whispers of plots against Lord Mayor Tomas by brothers of the R.I.C.

But now the curtain’s thrown back, light replaces the black, new life fills the streets

The war long past, Shandon’s Bells give blast, and the bells toll not for thee.

And away the years melt, as if the sound of the bells the distant past awakens,

And there’s the bright lad, wooden guitar in his hands, who aspired to such greatness.

Just barely past ten, so full of passion, he listens to the Armed Forces station

Where jazzmen blow and bluesmen strum and hold his rapt attention.

Below in the streets the air is replete with sounds of the busy day

The Shawlies call from their market stalls for sweets at Hadji Bey’s.

Staff of Thompson’s Bakery

The crowd wanders about as the Palace lets out, smelling of popcorn and Thompsons cake.

And the young lad stops at O’Brien’s shop for a Knickerbocker Glory or 99 flake.

Chocolate Easter eggs are poured above the Ice Cream Parlour, bags of treats nestled within.

Old Lowery’s Music Hall and Thompson’s Swiss Roll, by Easter Sunday both have arisen.

Atop the Examiner’s crown, the vast city surrounds, the proud son with guitar held dear.

The winner of fortune, T.V. talent competition, Roy Croft, the fabled compere.

Rory Gallagher on the roof of the Cork Examiner – 1961

Just a lad of North Mon, with brother on drums, he plays the school hall dances,

And charms the lads and lithesome lasses despite Christian Brothers glances.

Joins at 15 the Silver Star Ceili, who’ve traded fiddle ’n box for guitar wailing,

And travels to gigs throughout the land calling themselves the Fontana Showband

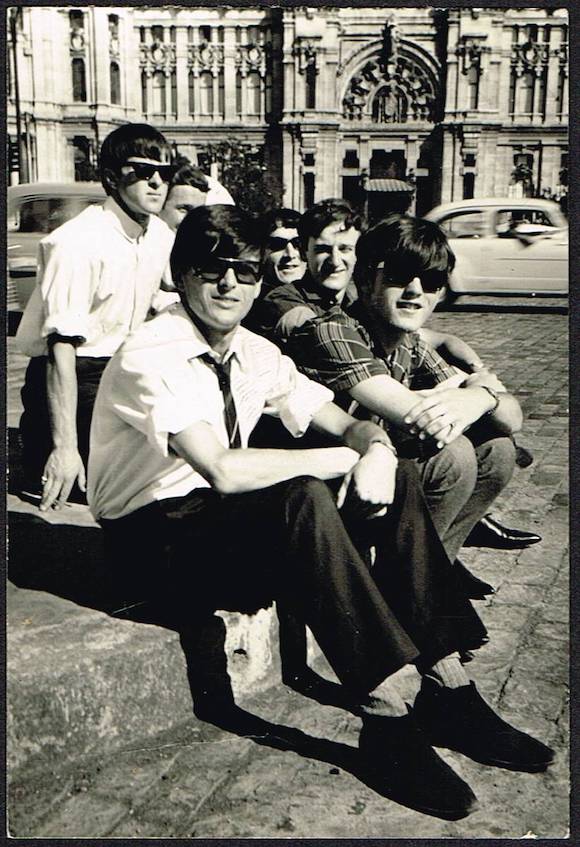

From the Arcadia in Cork to a dance hall in Dingle, Rory makes such an Impact,

That across the seas he goes, green budgie in tow, to Madrid then a London club residence.

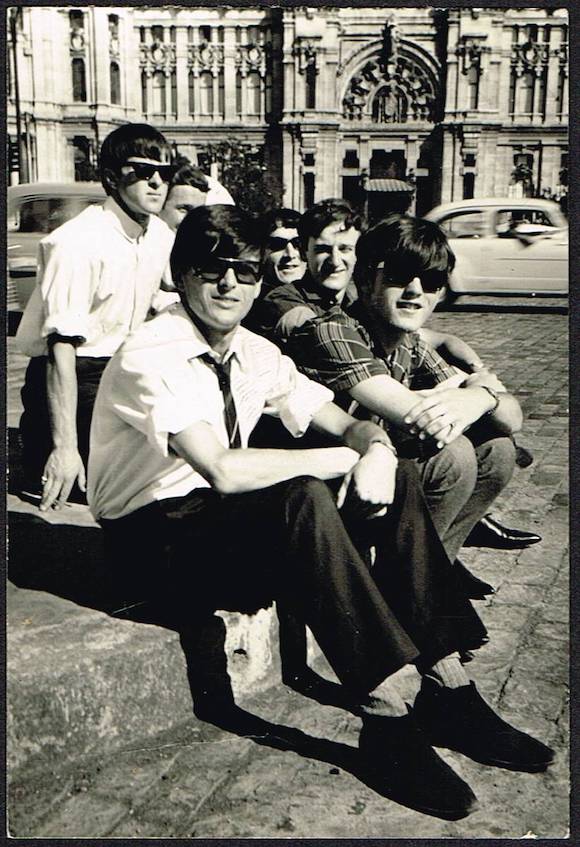

Impact Showband in Madrid in 1965

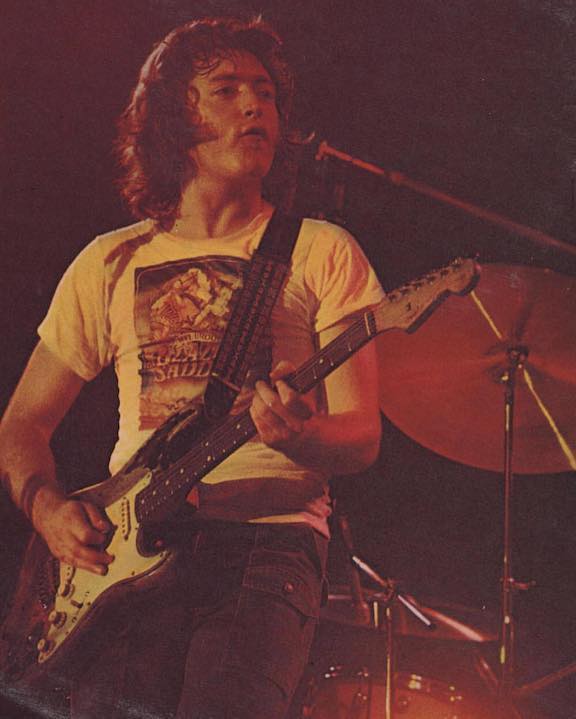

His name fast growing, he prowls the stage glowing, a caged lion deaf to the cheers,

With long hair flying, the young girls deeply sighing as he sings the “Valley of Tears.”

But he’s already found the love of his life, a sixty-one Stratocast Fender

Bought on the quay, a Showband returnee, from Crowley’s, a Lee-side vendor.

Long fingers caressing, no lassie so fetching as the curves of that sunburst axe

With dirty chunk riffs and searing hot licks ringing out from that body electric.

Like Beatles before him, the German clubs call him, the Sister Sirens of yore,

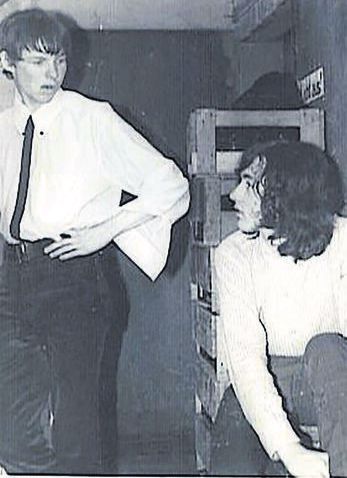

With the remains of the band, Johnny C. and Tobin, he sets off for that distant shore.

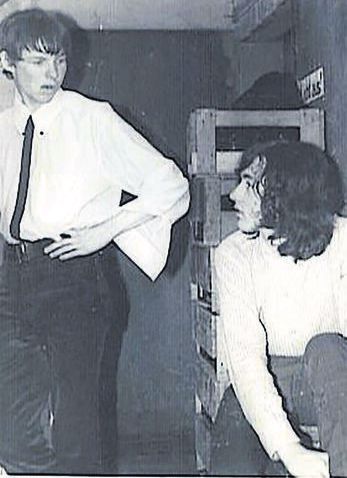

Johnny Campbell and Rory Gallagher – Hamburg 1966

A three week deal as a Fendermen fill, at the Big Apple playing rhythm & blues,

And there his craft grew in that crucible stew in the noise, the smoke and the brews.

Two local lads from the Axils band, Norman and Eric he takes on the road

And together the three play high octane R&B, taking the rebel county by storm.

Wherever they play, the silence gives way to cheers from the approving crowd

And their reputation grows like a blossoming rose, fame growing by leaps ’n bounds.

The path that they tread, like the roots of a tree spread far away to the distant lands end,

And the Tendrils take hold in the rich Irish soil, and nurture that burgeoning stem.

One tendril creeps north along the wild Atlantic coast to Derry by way of the Burren,

As if retracing the steps a young family once left by the banks of the river Erne.

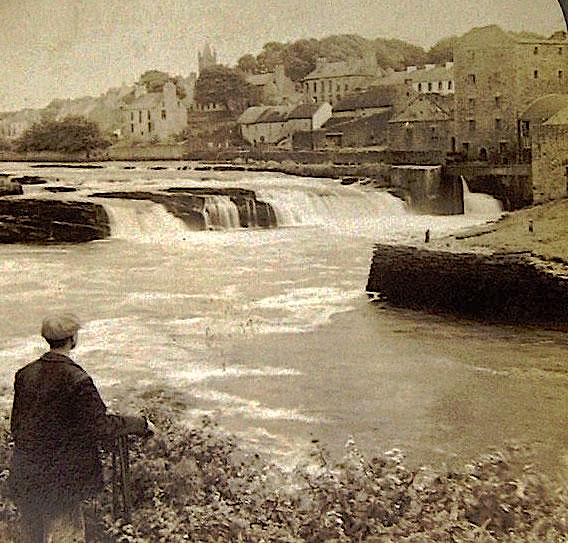

On a mill town step with babe at the hip she looks towards the river bend.

And pictures her man on the faraway dam testing strength in the hardened cement.

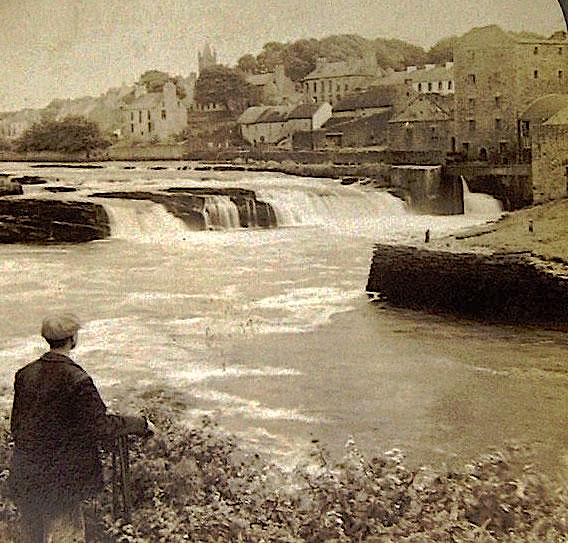

Was it there at the bend of the fast rushing Erne that the devil struck his deal?

And saw the death throes of the Falls of Assaroe for the price of a sparking joule?

Falls of Assaroe

For gone are the days when the salmon once played and fishermen cast their lures;

Now the river runs thin and the mist and the din of the roaring Erne is no more.

The men left town to find work down the line, young mother and child rode north

On a narrow gauge rail to the banks of the Foyle, to Granny’s house on Orchards Row

Many years have passed since that young mother cast her eyes to the faraway dam.

The babe now a man travels the roads with his band, “Taste the Goodness” writ on the mat.

The band finds a home in Club Rado, made Fam by the silky voiced Van,

But a grifter named Eddie turns love into envy while stealing the name of the band.

What a band they were, signed to Polydor, with John and Charlie the new big three,

Breaking box office records, denim and plaid de rigueur in the lines at the London Marquee!

“The second coming of Cream!”, the newspapers screamed, as they climbed to dizzying heights,

But the band fell apart as their album starts to chart, their swan song, the Isle of Wight.

“Rory’s to blame!” they cry in dismay. “Taste Splits!” splashed on the magazine cover

And he retreats deep inside stung by the bark and the bile and finds solace in his steel-stringed lover.

Was it there all alone in a London far from home where he plotted his rise from the ashes?

And taking his pain he turned inward and gained the power of the jewel of Abraxas?

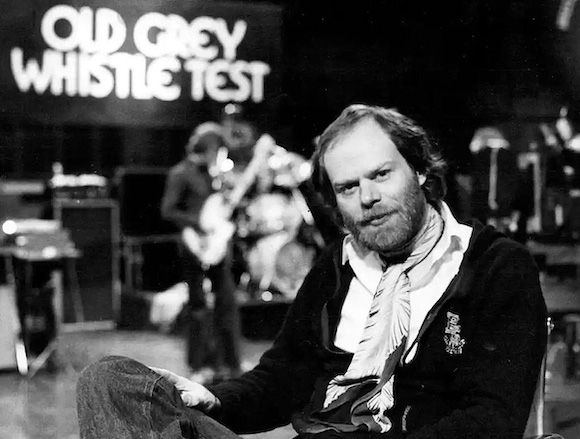

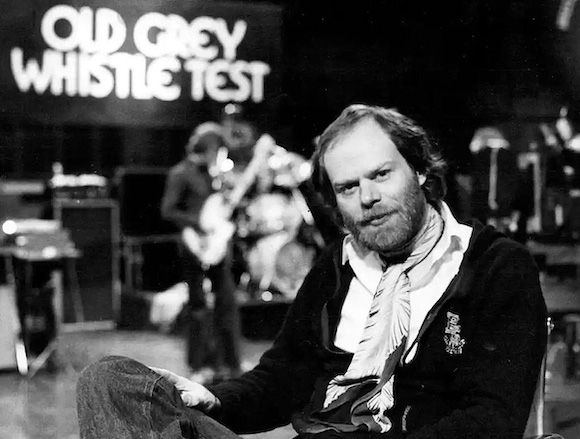

Whispering Bob

No Faustian gain just the sweat and the pain striving to be one of London’s best,

The darling of Peel, Whispering Bob strikes a deal with the Old Grey and their Whistle Test.

Does he know what it means to that island green, how proud they are of his success?

He’s one of their own, Corkonian grown, rebel county and Catholic blessed

Did he see the look in their eye, the love undisguised in the faces from Shankill and Falls?

The Troubles short rest in the fast beating breasts of the fans at the Ulster Hall?

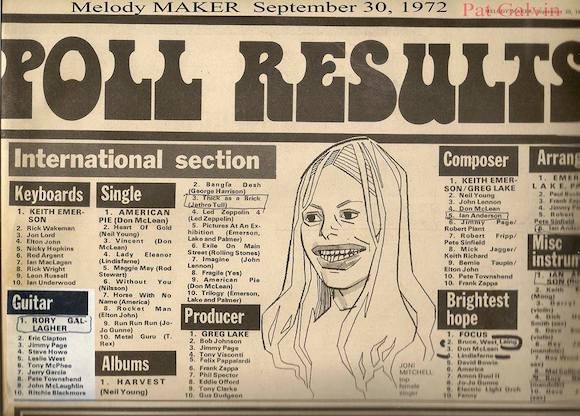

Just Paddy or Mick to the world large writ, yet Rory broke free from the mold

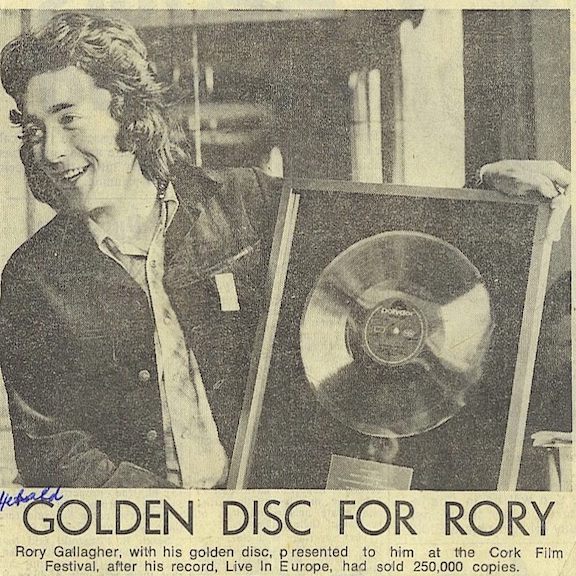

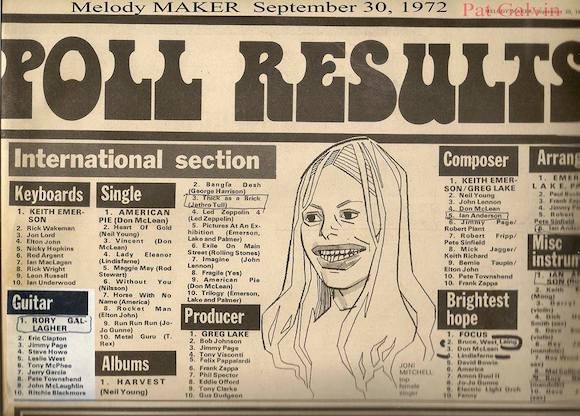

Beating out Clapton, guitar God of Britain, for top guitarist in the Melody poll.

1972 Melody Maker Poll

Epilogue

In Wexford town, between the sky and the ground, a small pub hugs the harbor shoreline,

And there the gull makes, a windward tack it doth take, from its perch on the old bridge sign.

And alights on the ledge of the windowed frontage, looming large in the smokey glass

A mariner’s demon, harbinger to seamen, a bug-eyed stare at the imbibing mass.

In the midst of the craic, an old punter sits back caressing his paddy and pint.

And through an alcohol haze he recalls the bright days of the what ifs and what mights.

The boards the lad tread with the stars in his head, took him to the very brink

Of fortune and fame, a rock god untamed, but in truth the boards did shrink.

As the years fly past, the fame doesn’t last and soon there’s none to remember

Those days long ago, now a trip down crow road, and death has claimed yet another.

St. Oliver’s Cemetery

The End

Share on Facebook