Aug 21 2011

Wheels Within His Master’s Wheels: An Interview with Elliot Mazer — Part Two

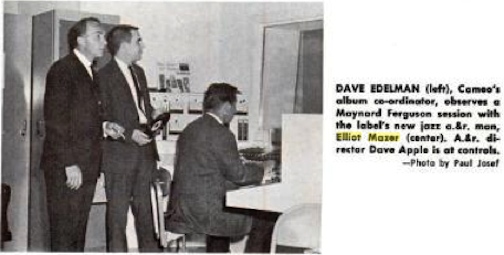

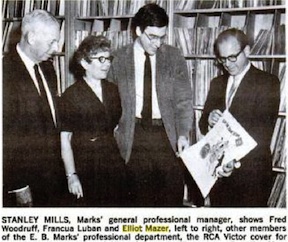

To call Elliot Mazer a famous record producer is like calling the grass green or the sky blue. While true, it doesn’t begin to do justice to the many other things he has accomplished in his 40 plus years in the music industry. Although he is most noted for having produced albums for such music icons as Neil Young, Linda Ronstadt, and Janis Joplin, he has also been instrumental in bringing to the industry important innovations such as “D-Zap” – a device for musicians and recording personnel that detects shock hazards, and the AirCheck monitoring system, which automates the identification of songs and commercial jingles on radio and television.

He was there at the birth and development of the digital music era, serving as a consultant to Stanford University’s Computer Center for Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) and designing the world’s first digital recording studio. He served as Senior Vice President of New Business Development for Radio Computing Services, and has been an adviser for such organizations as: Genaudio Inc, SESAC, Sezmi Corp, as well as working with the Warner Music Group on their Archive Project. Over the past few years he’s taken up (part time) residence in the hallowed halls of academia, sharing his knowledge and experiences of the music industry as a visiting professor to several colleges in North Carolina while continuing to produce various artists.

Recently I had the opportunity to ask Elliot a bit about his incredible career and in particular his work with legendary Irishman, Rory Gallagher:

Part Two: His Master’s Wheels

Shadowplays: Elliot, you’ve recorded Bob Dylan at the Isle of Wight, The Band at Winterland, and you’ve gone on the road to record numerous live concerts, in particular Neil Young. What are some of the difficulties in getting a good recording in that kind of setting?

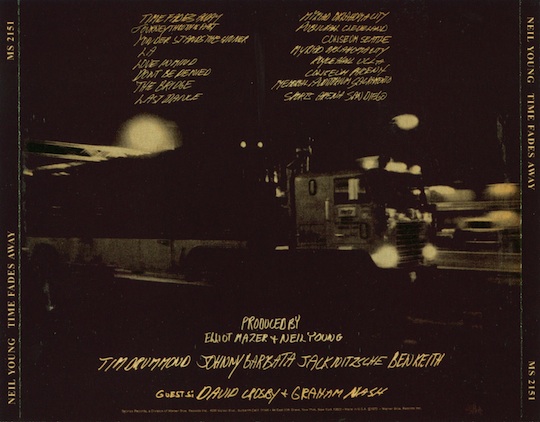

Elliot Mazer: I love live recording, whether it is on-stage or in a studio. In both cases you need to have your gear in place and working perfectly before the artist starts. At the Isle Of Wight, we used the Pye mobile and the engineer was Bob Auger. Glyn Johns and I were in the truck with Bob. His desk was a 16 fader Neve. It worked and sounded great. Bob was an amazing live engineer. A few years later I was producing a Jack Nitzsche album in a church in London. Bob had the same Neve desk but by then all the lettering had worn off. The thing sounded great and had no problems. In 1973 Neil and I were working on the band for his Time Fades Away tour. He wanted to record a few shows. I decided to build a truck. Jim Guercio who owned Caribo Ranch and I talked about his Neve desk, which he loved. Jim gave me the name of the Neve guy in New York. He found a twin of Jim’s desk at the factory in England. That desk was built for a client in Spain who defaulted. I purchased it and had it sent to Nashville where we were building the truck. A while later a truck pulls up and a gentleman in a suit greets us saying he was David Neve, Rupert’s brother and that he had our desk.

Shadowplays: You can see the Neve equipped truck on the cover of Neil’s album, Time Fades Away. In the Fall of ’73 the truck traveled to San Francisco, taking up residence at Alembic Studios on Brady Street, the old Grateful Dead recording studio. Several months later Wheels bought out Alembic and the more permanent facility of His Master’s Wheels was born. Was the truck ever used again for recording live gigs after the move to S.F. and the installation of the truck’s sound equipment into the studio? Seems a daunting task to break down the studio for transport on the truck. Whatever became of the truck?

Elliot Mazer: His Master’s Wheels was a wonderful studio. We did albums there with Rory (see below), Frankie Miller, The Dead, David Grisman, and I mixed CSNY and Neil Young stuff there too. It was easy to move the equipment in and out of the studio to the truck. We used that truck a lot. It did the CSNY 1974 tour and that stuff is amazing. I recorded a Leonard Bernstein production of Haydn’s Mass In Time Of War in the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. That was before Nixon’s inauguration and it was a protest about Nixon. The truck is safely tucked away near Neil Young’s studio and it is used by John Nowland as a restoration and archiving facility.

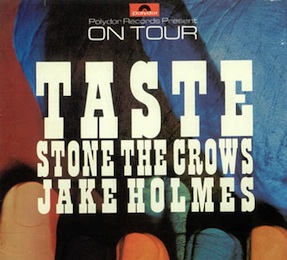

Shadowplays: During the summer of ’76, Rory headed off to Musicland Studios in Munchen, Germany to record his second album for Chrysalis, Calling Card. For the first time since his Taste days, he allowed someone else to produce his album, choosing Deep Purple’s bassist, Roger Glover who had done some production work with the Spencer Davis Group, Elf and Nazereth. Not satisfied with Glover’s mixes, Rory asks for your help. Do you remember the exact circumstances?

Elliot Mazer: Donal or Chrysalis called me after they finished in Munich. Rory did not like the mix. They sent me the tapes and I did a new mix. I was not impressed with that album. I mixed it as an American rock album. Rory did not like that either. Somebody else mixed it in London.

Shadowplays: Chris Kimsey did the final remix. He did a lot of work for The Rolling Stones. Did Rory say why he didn’t use yours?

Elliot Mazer: I do not know why. I presume that Rory hears his records as a rockin’ trio. If anything deviates from that he gets upset.

Shadowplays: The album wasn’t released until late October, in time for another American tour. It was around this time that you had begun preparing for Robbie Robertson and The Band’s final project, a recording of their final gig together, at the venue where it all started for them, the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. Martin Scorsese filmed the show for the documentary The Last Waltz. You were chief recording engineer for the project. I thought that documentary was mesmerizing. Interestingly, Rory and his band had just played Winterland the week before.

Rory Gallagher at the Winterland Ballroom, San Francisco, CA

photo courtesy of Ben Upham at Magical Moments Photos and Ben Upham Fine Art Photography

In McAvoy’s book, Riding Shotgun, Gerry states that it was at this time that the band first met you. Rory had just headlined there (with Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet band in support) and that it was the last show at Winterland before preparations got underway for filming of The Band’s last show there. Gerry goes on to say that the show’s promoter, Bill Graham, had asked Rory to join the line-up. Apparently Robbie Robertson was a fan of Rory’s and had asked if Rory might be interested. Robbie doesn’t remember this however and some of Gerry’s remembrances have been called into question by Rory’s brother, Donal. Do you remember meeting with Rory and his band during this time?

Elliot Mazer: Yes I did meet with Rory and the band around that time. I doubt that Bill Graham would have asked Rory or anybody to play the Last Waltz. The cast had been established months before the show. Robbie and Marty Scorsese planned that show a long time before that night.

Shadowplays: Even though he did not use your mixes on Calling Card, Rory did decide to have you produce his next studio album. Can you recall the initial contact for the album. Did Rory or Donal call you up to discuss the possibility of producing an album for him in the U.S. ? I understand you were in England at the time. What were you doing in England?

Elliot Mazer: I don’t remember why I was in London. Roy Eldridge or Chris called me to sound me out. I was reticent about working with him after Calling Card. I felt that Rory saw himself as a front man in a trio.

Shadowplays: Rory was keen on producing an American rock album. He brought you to Cork to discuss the project along with Roy Eldridge, managing director at Chrysalis. Roy Eldridge knew Rory from his days as a journalist for Melody Maker. Can you explain what Rory’s ideas/concepts for this album were to be? The “Why” of making an album that you discuss with your students.

Elliot Mazer: I don’t remember the exact things we talked about. I know I would have told him about my reservations. To me, Rory had two big styles. One is American Rock n’ Roll. The other is his great love of and knowledge of Southern Blues. I love the middle to late 60’s music coming from Memphis and Muscle Shoals. To me, it captured the best of both worlds. The rhythm sections were fat, the vocals were big and present and guitars, keyboards and horns were in the middle.

Shadowplays: Yes, Rory had two very big styles. Junior Lee Klegseth, former guitarist for RedHot Blues Band once told me that categorizing Rory as a Blues-Rock guitarist was a bit misleading. He was a great Rock guitarist AND he was a great Blues guitarist — not just the intersection of the two. In December of 1977 Rory comes to your studio in San Francisco after an extended world tour. You set him up at the Sunset Marquis Hotel along with a reel-to-reel so he can listen to each days mix. Did you notice any fatigue in the band after such a long tour? How long before the mixing sessions started bogging down?

Elliot Mazer: The time is correct. But we were in San Francisco and that hotel is in LA. Rory was in a private apartment in SF. The band was great to work with. I did not notice any fatigue or problems with any of them. We were recording mostly live in the studio and doing overdubs for around a month.

Mixing started almost immediately after recording. We had no time to reflect or plan the mix.

Shadowplays: Yes, you set Rory and band up in private apartments in Pacific Heights overlooking San Francisco harbor. It wasn’t until after he had returned from Cork for the remixes that he stayed at the Sunset Marquis in LA. Was the pressure from Chrysalis to produce a “hit” album palpable? As well as getting back on the road to promote it? With the previous album, “Calling Card” Donal tells the story of Chrysalis’ attempt to edit “Edged in Blue” (without Rory’s permission) in order to make it more radio friendly.

Elliot Mazer: Chrysalis was encouraging and helpful. Roger Watson came by on occasion and Donal was there a lot too. Labels and managers are always under pressure to make hits, get them out fast, and get the acts back on the road.

Shadowplays: Could you see any tension between band members? Rory’s bassist Gerry McAvoy stated that the band had divided into two camps: Lou & Rod and Rory & Gerry.

Elliot Mazer: That might have been the case, but I never felt that. Those guys played wonderfully and helped Rory.

Shadowplays: Roger Glover mentioned how wonderfully loyal Rory’s band mates were to him. Can you give us an example of how a typical recording session went?

Elliot Mazer: We would decide on which tune to do next. Rory always had a plan in mind. We setup the studio and get a balance for the earphones and make sure everybody was comfortable. The sessions were smooth and exciting. Rory played a lot of different guitars and Martin Fiero a wonderful Sax player played on a few tunes. I remember all of us enjoying the hard work.

Shadowplays: Martin Fiero had a long association with Jerry Garcia and the greater Dead family. Several Dead websites even gave notice of the impending release of Notes from San Francisco because of the “Meester” playing on a couple of the tracks. In the early years Rory played a little bit of Sax. Gerry McAvoy states there were a lot of bitter disagreements between Rory and Roger Glover during the recording and mixing of the album Calling Card. Gerry says that Rory would purposely do stuff to irritate Roger. Did this happen in San Francisco too?

Elliot Mazer: No, Rory was polite and kind and helpful all the time.

Shadowplays: You mentioned that during Rory’s stay in San Francisco that you and he went to the infamous final show of the Sex Pistols at Winterland, and how struck he was at their raw energy. Donal has stated that Rory was already having second thoughts during the Christmas break about the SF sessions, but do you think this show was the veritable “final nail on the coffin” that sealed Rory’s decision to scrap the album, scrap the band, and return to a power trio?

Elliot Mazer: If Rory told Donal he was having second thoughts, somebody should have told me. There was never a time that anybody indicated that Rory was not pleased. He sang and played great, as did the other guys. That show was during the mix, which was a stressful time for us.

Shadowplays: At some point Rory decided that Robin Sylvester, sound engineer from several of his earlier albums might be able to lend a hand with the mixes. When did Robin come on board?

Elliot Mazer: Robin was fun to work with and it was good that he was there as he and Rory had a positive history. He came to our studio about a week into the mixing I think. Robin is a musician. He was an okay engineer but his ear was that of a musician.

Shadowplays: And did it seem to go better after Robin got there? Had you known/met Robin before this? I understand you worked with him in other projects later on.

Elliot Mazer: Things were a little better with him there. To me, the biggest problem was that Rory was not hearing this record sound like his other records. He was used to trio records and they were by nature thin. I was trying to make a competitive American rock/blues record that was more dense and fatter. Rory knew that sound from the music he was influenced by. But he was not hearing the feels of the Memphis rhythm sections in this music. But Rory was an Irishman that loved rock and blues. I liked that his musicians came up with their own styles and that suited Rory just fine.

Shadowplays: You mentioned once that there is a fundamental difference in how the British and American studio engineers capture/manipulate the sound in the recording process. Could you elaborate? And this would be one reason why Rory would be more comfortable with Robin’s input in the mixes?

Elliot Mazer: British engineers were used to a lot of processing in recording and mixing. That made it easier to mix. Mostly Brit engineers turned knobs and created non-literal sounds. British studios usually had tons of expensive condenser mikes while US studios had a large variety of mikes. American engineers would choose a mike to suit any particular instrument. Brit engineers put up mikes and added tons of eq and compression to get desired sounds. American engineers tended make things sound more literal. American engineers mostly reproduced real sounds and made them work in the context of a mix.

Shadowplays: In the end, Rory decides to bin the album altogether. His copy of the mastered disc literally dropped into the trash can — the “American Rock Album” was just not there for him, at least not with the current band mates. Despite his brother Donal’s pleas for further remixing, Rory has had enough, and flew back home. You mentioned that his last words to you were at a mastering session at Kendun, saying that he didn’t like the high-hat sound. How did you find out that Rory had pulled the plug on the album? What was the reaction of the label? You mentioned that you had given a copy to Chris Wright.

Elliot Mazer: I think Chris called me to say the project was dead. He had heard it and liked it.

Shadowplays: 33 years later, Rory’s brother Donal (and Donal’s son Daniel) decide to finally release the San Francisco album albeit remixed. After listening to the newest mixes how do you think it stands up to the original master of the album you produced for Rory?

Elliot Mazer: I like the new album. It is enjoyable. Mixing is like making a curry. Everybody has a different recipe. The person that did these mixes is not a musician. Fuel To The Fire and Cruise On Out are my mixes. Out On Tiles and Cut A Dash are the mixes I gave to Rory for review. They are rough.

Shadowplays: I understand the original track listing is different from the new release. How so?

Elliot Mazer: Rory and I had specific sequence. His nephew changed it for some reason. I had suggested putting the “B” side first and keep all the songs in order. We sequence albums carefully so that they flow nicely. Keys, Tempo and other aspects are taken into account.

Side A

- Overnight Bag

- Cruise On Out

- Brute Force and Ignorance

- Fuel to The Fire

Side B

- Rue The Day

- Mississippi Sheiks

- Persuasion

- B-Girl

- Wheels Within Wheels

Shadowplays: One of the big surprises for me was “Persuasion”. I thought that it might have done well on the charts, definitely more of a “pop” sound than what I’m use to hearing from a Rory song. The song definitely fits better on this album than as the bonus track for Deuce. I also like the electric alternate version of Wheels within Wheels, and perhaps it too might have found some play on the radio. I think I’d rather have this song end the album rather than the two unfinished songs, Cut A Dash, and On the Tiles. Do you think any of the songs could have charted in the U.S.?

Elliot Mazer: I don’t think any of those tunes would have been a hit. They would have gotten him a lot of radio play.

Shadowplays: You stated in an interview once that when you first heard Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” you knew it would be a No.1 hit. That it had it all. What was missing with Rory? How do you think the San Francisco album would have fared in 1978? To me it has a Muscle Shoals sound to it that I quite like. WAS it what Rory needed to break into the U.S. market? Do you think that given more time, and without the pressures from the label to package and promote a new Rory album and tour that things could have worked themselves out and Rory would have had his American album?

Elliot Mazer: Part of me thinks that given more time, Rory and I would have come to an agreement about the way it should sound. I gave him 15ips rough mixes every time we cut a new tune or did an overdub. I was well aware of his nature to dislike something after a while. I was trying to avoid a situation like the one we had with Calling Card in which the artist did not agree with my idea of how a record should sound. I had a good relationship with Chrysalis and wanted to do a big record for them.

Rory was not drinking during the production of this record. I had asked him to be clear headed. He had a different kind of energy. I felt that his singing was wonderful as was his guitar playing. There are lots of good guitar parts that are not balanced properly in this new mix. Listen to how cool the guitars on Fuel To The Fire sound. On the surface you hear his main guitar but there is a lot cool stuff going on underneath. Lou’s keyboard parts are good but they overpower many of Rory’s parts. The bass is not properly balanced too.

Shadowplays: In the end, Rory’s “American album” was not to be, and perhaps this was Rory’s last big chance to crack the American market. And while that was something he ideally wanted to do, he was not willing to change his sound to accommodate what others felt he should do. In some ways that makes him the ultimate guitar hero. Do you have any additional thoughts on his career or his life, from either your professional standpoint or your personal regards?

Elliot Mazer: Rory positioned himself in such a way to become hugely successful in Europe and Japan. In the US, you need to get hits on the radio to really break through. And you need great sounding aggressive records that sound amazing no matter where they are played.

I really enjoyed hearing him play and working with him. He was a wonderful spirit.

Shadowplays: Elliot, Thanks for taking the time to talk about your life and your associations with Rory.