Garth Cartwright

Garth CartwrightGarth Cartwright is a London-based, music and arts journalist with three books under his belt and regular contributions to various UK publications such as The Guardian, Telegraph, and Sunday Times. In 1995 he won the Guardian Music Writing Award. In his latest article for the Sunday Times, “The Dark Side of the Sun,” Garth talks with Donal Gallagher, brother to the late, great blues and rock guitarist Rory Gallagher. For those unable to get their hands on the latest issue of the Sunday Times I’ve posted the full article below. Many thanks to Garth for allowing me to post it to my blog. And be sure to check out his website at garthcartwright.com!

The Dark Side of the Sun

(Garth Cartwright meets the brother for whom Rory Gallagher’s death is still raw)

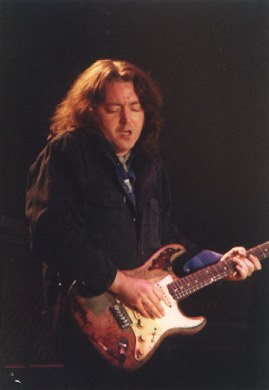

© Erica Echenberg

Cork City has the blues. An air of deprivation lingering across the city’s Celtic Tiger-era edifices may explain why Cork strongly embraces the memory of Rory Gallagher, its most famous son and a bluesman of extraordinary talent.

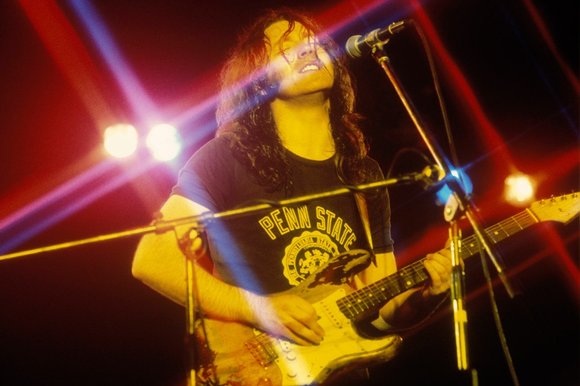

Rory Gallagher (1948-1995) was the Irish Republic’s first rock star. With his blazing guitar and beatific smile Gallagher was the Gaelic guitar hero. And in his humble manner very much a musician of the people. Yet by the 90s Rory was a reclusive paranoid, his torso swollen by steroids. When he died (from complications following a liver transplant) an outpouring of grief followed: Van Morrison, U2, Johnny Marr, Brian May and Slash all saluted Rory’s musical brilliance and personal generosity. Now, with a comprehensive reissue of his solo albums underway, Gallagher’s legacy is finally being celebrated. Thus I’m walking the streets of Cork with the man who knew Rory best – his brother Donal Gallagher.

“Talking about Rory can get a bit heated,” says Donal, noting how football fans in Cork and Donegal recently clashed over which team “owned” Rory’s allegiance. Such are the tribulations surrounding a local legend. “I’m constantly encountering fans from all around the world,” he adds. “And they’re often youngsters. You-Tube’s introduced Rory to a new generation.”

Donal and Rory grew up sharing the same bedroom above a Cork pub. A year Rory’s junior, Donal became Rory’s roadie. Then tour manager. Then manager. And now he looks after the estate. He truly is his brother’s keeper. Fortuitously, Rory owned his solo recordings and Donal and his son Daniel are overseeing the reissue of Rory’s first eleven solo albums (1971-82). Listen to the young gun – strong songs, warm vocals and the guitar playing . . . the guitar playing is just in-cred-i-ble. Outside of Jimi Hendrix and Peter Green no other rock guitarist has managed to convey such warmth, finesse and wild excitement. Yet like Hendrix and Green, Gallagher’s talent could not protect him from the storms of life.

“Rory could build a guitar but he couldn’t boil an egg,” says Donal. “Music was everything to him. Once he started playing guitar as a boy he ignored everything else. Just stayed in his room practicing and practicing.”

Thus Rory’s social skills remained underdeveloped.

“Rory found it impossible to form lasting bonds with people,” notes Donal. “He was his own worst enemy. Playing music was his all. Off the road he didn’t know what to do with himself.”

Rory showed a propensity and passion for music as a child. In his early teens he convinced his mother to buy him a second-hand Fender Stratocaster on hire purchase. Aged 15 he joined the Fontana Showband, working dances across Ireland and England before heading out to Hamburg’s Star Club. The pimps, prostitutes and merchant seamen who frequented the Star hailed Rory as the most exciting rocker since The Beatles learnt their trade there. Forming Taste, he based himself in Belfast. Word quickly spread of the teenage prodigy. Management, a contract with Polydor and the inevitable shift to London followed.

Taste lit up London – John Lennon described them as “the only band worth seeing” while Eric Clapton invited Taste to support Cream’s Royal Albert Hall farewell – and their two albums proved international hits. Yet after playing 1970’s Isle Of Wight Festival Rory quit: the band’s manager had him on £15 a week wages and Gallagher chose to walk away rather than fight.

“We were living in Earls Court bedsits,” recalls Donal. “Taste were in the charts, headlining major festivals, but not seeing the proceeds. Later, when I became Rory’s manager, I insisted we go to court to get the royalties. Even then Rory was reluctant. He didn’t like conflict.”

Rory’s gentle nature made him an icon of peace and goodwill in a divided Ireland. As The Troubles worsened Rory became the only major musician willing to tour Northern Ireland, his concerts cathartic events where Catholics and Protestants could gather in a conflict-free arena.

“Rory emphasized that he would not take sides in the dispute,” says Donal. “He insisted we tour there because he believed in the positive power of music. While Tony Palmer filmed his 1974 Irish tour he tried to push Rory into taking a stance but Rory refused. He was there to bring joy not politics.”

Palmer’s film Irish Tour ’74 remains one of the great concert movies while the resulting live album captured Rory at his most exciting and inspired. No wonder The Rolling Stones, then searching for a guitarist to replace Mick Taylor, invited Rory to join.

“Rory flew to their base in Holland and stayed three days,” says Donal. “But Keith was too stoned to play and Rory had a Japanese tour lined up. He left without even a ‘goodbye’. At the time Rory was outselling the Stones across Europe so it’s not like he needed the gig. But, in retrospect, I wish he had communicated more with them as it could have worked. He and Charlie Watts would have got on very well – both being consummate musicians and jazz fans.”

Rory certainly didn’t need The Stones for money: he sold over thirty million albums and innumerable concert tickets. Yet perhaps the camaraderie of playing in The Stones would have helped calm his anxieties. A fear of flying fed phobias that developed, in the 80s, into hypochondria. Amoral GPs wrote him prescription after prescription. Addicted to pills and liking a drink, Rory’s health collapsed.

“Rory wouldn’t smoke a joint,” says Donal, “but he self-medicated with prescription pills. And that caused so much damage. On tour I once went through his baggage and found a hornet’s nest of pills. I checked with a German pharmacist who said ‘if he’s mixing these with alcohol it’s the devil’s brew’.”

Donal’s had a long time to deal with losing Rory but his frustration and grief remain palpable.

“Rory got more and more paranoid. He played Montreux Jazz Festival with Bob Dylan in 1994 and Dylan, who had always been a fan, came up after the show and said how he would love to record with Rory. I thought ‘manna from heaven!’ and that this would be the fresh start we needed. That night Rory locked himself in the hotel’s penthouse and wouldn’t come out for three days.”

Donal swapped Rory’s prescription pills for homeopathic placebos. He confronted the GPs. He confronted Rory. He sent Rory home to mum in Cork. Too late: a liver transplant in early-1995 appeared successful but Rory’s rare blood type and shattered immune system lead to rejection. Like George Best, another Irish genius of the same generation, Rory Gallagher would die before his time.

“My wife wonders if Rory was autistic. That’s a possibility,” says Donal. “Anyway, what Rory achieved can’t be taken away. People love his music. Across the USA they’re rediscovering Rory for the first time since the 70s. In Paris there’s a Rue Rory Gallagher, Hamburg has a plaque, Dublin and Ballyshannon have statues. Fender’s Rory signature guitar is one of their best sellers. There’s a biopic in the works. It’s a bit like those old black bluesmen Rory loved so dearly – he’s more appreciated now than when he was alive.”

Garth Cartwright — garthcartwright.com

(published in the Sunday Times, September 30, 2012)

Share on Facebook