Aug 15 2011

Wheels Within His Master’s Wheels: An Interview with Elliot Mazer — Part One

To call Elliot Mazer a famous record producer is like calling the grass green or the sky blue. While true, it doesn’t begin to do justice to the many other things he has accomplished in his 40 plus years in the music industry. Although he is most noted for having produced albums for such music icons as Neil Young, Linda Ronstadt, and Janis Joplin, he has also been instrumental in bringing to the industry important innovations such as “D-Zap” – a device for musicians and recording personnel that detects shock hazards, and the AirCheck monitoring system, which automates the identification of songs and commercial jingles on radio and television.

He was there at the birth and development of the digital music era, serving as a consultant to Stanford University’s Computer Center for Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) and designing the world’s first digital recording studio. He served as Senior Vice President of New Business Development for Radio Computing Services, and has been an adviser for such organizations as: Genaudio Inc, SESAC, Sezmi Corp, as well as working with the Warner Music Group on their Archive Project. Over the past few years he’s taken up (part time) residence in the hallowed halls of academia, sharing his knowledge and experiences of the music industry as a visiting professor to several colleges in North Carolina while continuing to produce various artists.

Recently I had the opportunity to ask Elliot a bit about his incredible career and in particular his work with legendary Irishman, Rory Gallagher:

Part One: A Legendary Career

Shadowplays: Elliot, thanks for taking the time out of your busy schedule to answer a few questions. Are you still teaching at one of the Carolina colleges? I had read that you had been working with students at University of North Carolina – Asheville and at Elon University.

Elliot Mazer: My pleasure Milo. I am teaching at Elon University now. I love the idea of passing my experiences and knowledge onto students.

Shadowplays: That must be a very rewarding experience. Are these classes primarily for student musicians then? Giving them a broader understanding of the total recording process?

Elliot Mazer: The classes are part of the Music Department and are attended by students from other departments too. I teach Recording Arts which is about the “why” of recording and I teach students about how they can approach promoting, marketing and selling their music today.

Shadowplays: Recording music has changed dramatically over the years. With relatively cheap apps like Apple’s Logic Studio, or even its freebie app, Garage Band it seems that almost anyone can record professional sounding music now. The downside is that, not everyone is meant to be a recording artist. Reminds me of that old put down that’s been attributed to so many musicians over the years: “He could make that guitar really talk. It’s a pity he had nothing to say.”

Elliot Mazer: The proliferation of inexpensive recording systems has led to massive number of terrible sounding recordings of music nobody cares about. Having a hammer does not necessarily mean you can build a house. Songs are the foundation of all records. It is easier to learn how to run ProTools than it is to write a song people care about.

Shadowplays: Are you still producing albums today? Out of your home studio, or do you rent time at a commercial studio? With the advent of Pro Tools coupled with the drop in price of microprocessors and hard drives the commercial recording studio seems to be going the way of the dinosaur don’t you think? Or are they still a viable option? I imagine their business model had to change dramatically to stay solvent.

Elliot Mazer:I am producing music in commercial and homes studios. I do not record in my personal studio. It is a post-production facility. I use Logic with UAD processing cards. ProTools became another dinosaur. It is easy to use, expensive and it does not sound that good. My favorite studio is Quad Sound Studios in Nashville. It is the studio we built in the early 70’s. QSS has been modernized and it is still a wonderful place for me to work.

Shadowplays: The recording studio was a way for musicians to meet up, find each other, check out what others were doing. It was more than just four walls and lots of expensive equipment, but also a network of connections to various session players and recording artists. Didn’t your studio in Nashville provide most of the backing musicians for Neil Young’s Harvest album? Wasn’t the band Area Code 615 a collection of local Nashville musicians? I remember them from the BBC show, Old Grey Whistle Test. The opening music was Area Code 615’s “Stone Fox Chase.”

Elliot Mazer: Area Code 615 consisted of 9 Nashville Musicians and me. Kenny Buttrey, Wayne Moss and I put it together. Kenny and I shared production credits on the first album. I had loved working with those guys over the past few years. I asked them if they wanted to do an instrumental album. We cut a few songs and I played if for a few labels in New York, Polydor signed us. Each of us brought a tune to the project. Bobby Thompson, banjo, had learned “Classical Gas”. He and Charlie McCoy worked up the arrangement. We cut it mostly live and in 3 sections. It took most of one day to cut that and put it together. Most of the album was cut live in the studio, solos and all. Those guys were fantastic players who loved to play good music. The 615 Band played the Johnny Cash TV show and we did a weekend at the Fillmore West. A huge number of SF (Bay Area) musicians came to the gig. The second album included “Stone Fox Chase” which was the theme of Old Grey Whistle Test.

I played the first album for Bob Dylan in Woodstock. He loved our version of “Just Like A Woman” and he asked why there was only one of his tunes and two Beatle songs on the album. George Harrison told me that he loved 615.

Harvest was recorded in Quad Studios. The band consisted of musicians I had worked with previously. I met Neil the night before we started. He had heard of Area Code 615 and wanted to see how they would fit with him in the studio. That album was cut live in the studio. We added backing vocals. The rest of the music was cut live.

Shadowplays: As private home studios become more in vogue, it seems you won’t get that interaction between musicians that you got in the old studio days. Would “Tenor Madness,” that famous collaboration of Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, have happened in this day and age?

Elliot Mazer: Rudy Van Gelder’s first studio was in his home in Hackensack, New Jersey. It was a home studio. He cut an amazing number of great records there by Miles Davis, Coltrane and others.

Yes collaboration produces amazing results. Most young people with home systems, spend days recording a song. They either play drums or use loops, same with the other instruments. When they get it to a point where it is mostly complete it sounds flat and boring. They think that adding more parts will fix that. Yes, putting a bunch of great musicians in a room can produce a wonderful result if the song (composition) is compelling.

Shadowplays: “Tenor Madness” was done at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio for Prestige Records, and Prestige was where you first got your feet wet in the recording industry. How did you get your foot in the door? In a posting on a Bob Dylan forum a woman named Joan said she lived across the street from you in New Jersey and was a cousin of Bob Weinstock. Her family and yours used to vacation together.

Elliot Mazer: Yes, Joan’s brother Andy and I were close friends. Their father was a fanatical New York Yankees Fan. Bob Weinstock lived down the street from us. I met him in the Sam Goody Record store that I was working in. Bob hired me away from Sam Goody. My first job was organizing the tape library in the basement and delivering records to radio stations. I found a collection of John Coltrane outtakes, that I put together, Standard Coltrane which is still available.

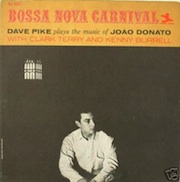

Shadowplays: The first album you produced for Prestige Records was Dave Pike’s “Bossa Nova Carnival” in 1962. Bossa Nova style was big back then wasn’t it? How did the record do?

Elliot Mazer: I met Dave Pike who had met Joao Donato in Brazil. Bob Weinstock told me to cut a record with him. Clark Terry, Kenny Burrell and Dizzy Gillespie’s bass player and drummer played with Dave playing a vibraphone. The record was good and I think it did pretty well. I loved working with Clark and I wound up producing two of his albums a few years later.

Shadowplays: Bob Weinstock founder of Prestige Records seems a bigger than life character. What was it like working for him and also his engineer Rudy Van Gelder? Many jazz sites list Rudy as the greatest recording engineer in jazz history. And Rudy’s still going strong, I saw where a new SACD of The Miles Davis Quintet was released recently with his name on it.

Elliot Mazer: Weinstock was an interesting person. . He loved music and could work with musicians. He was a brilliant on the stock market too. Rudy Van Gelder is an amazing engineer. His studio was designed by him and his wife. She was a student of Frank Lloyd Wright. Rudy kept a lot secrets and did not like people making suggestions or looking over his shoulder.

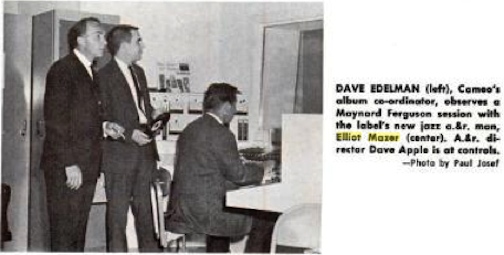

Shadowplays: After serving your time with Prestige Records you moved on to Cameo-Parkway.

Elliot Mazer: Cameo-Parkway was an independent label in Philadelphia. It was an amazing place. It had its own studio. There were songwriters, artists and musicians there all the time. The first studio, where they cut most of their early hits, had one mono machine and two stereo machines. They cut bass and drums first, then guitars, then keyboards, lead vocals, backing vocals each time on a new piece of tape which added one generation for each new part. By the time they had all that stuff recorded, you could not hear the drums. Often they were 8 tape copy generations down from the original. One more generation was added – drums and bass.

Shadowplays: Cameo was more of an R&B label wasn’t it? Philly soul? Your arrival at Cameo seemed to coincide with some Jazz players getting on board, players like Maynard Ferguson and Clark Terry? Clark Terry had played on your first record for Prestige, Bossa Nova Carnival.

Elliot Mazer: Yes, I was their jazz guy but I loved pop records and therefore wound up working with Chubby Checker. I did a demo there with Phil Ochs who was not signed but Cameo management did not like him. I produced a swing album with Chubby Checker. Sy Oliver was the arranger and the band was great.

Shadowplays: Cameo Records wasn’t able to make the transition to Rock ‘n Roll, and by 1967 had been gobbled up by Allen Klein and his company ABKCO. The first 45 I ever bought was “96 Tears” by Question Mark and the Mysterians. That was a Cameo production from 1966. Had you moved on by then?

Elliot Mazer: I had an office for them in New York. They turned down early Beatles, Searchers and Nashville Teens records. They did not understand that music.

Shadowplays: You also worked on the music of composers like Alex North and Nino Rota. Nino Rota scored those wonderful Fellini movies (he also did the Godfather scores). Was this after you had left Cameo?

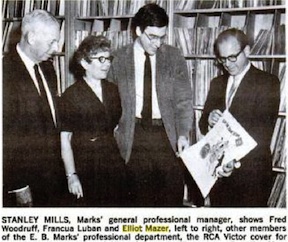

Elliot Mazer: I worked at E. B. Marks Music in New York after Cameo. I had met them through Arnold Shaw who was their Professional Manager. Arnold was an author and teacher too. Paul Simon worked there as a song plugger. I worked with songwriters, made demos and helped on soundtrack sessions and edits. I never met the Rota or The Maestro. I worked on their US releases.

Shadowplays: In 1970 you moved to Nashville and set up Quadrafonic Sound Studios with Norbert Putnam and David Briggs, a decidedly non-country music studio in a country music town. Why Nashville? I would have thought Memphis would have been the more likely choice considering your background in Jazz.

Elliot Mazer: My background was in folk, jazz, pop and R’n’B. I had worked in Nashville previously and loved the studios and musicians. It was a city that was/is about music. Country is a big part, but one can cut most any kind of music there. I had worked with David and Norbert on a bunch of cool albums. We were all in Area Code 615. Kenny Buttrey was the key to all of my efforts in Nashville. He was an extraordinary musician and person.

Shadowplays: Kenny Buttrey has a long list of credits on albums such as Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and Blonde on Blonde, and toured with Neil Young as a member of the Stray Gators . I read that Putnam & Briggs originally saw Quadrafonic more as a publishing house, but it quickly became one of the hottest studios around, no small thanks to the acts you were able to secure for the facility. How were you able to “grow” Quadrafonic so quickly?

Elliot Mazer: I liked the idea and plans for the studio. I invested in it and we three were partners. I had been busy producing various acts and I was able to do those records in our studio. I believe that the first thing I did there was mix the single version of Linda Ronstadt’s Long Long Time.

Shadowplays: Janet Furman (Furman Sound) said that you seemed to know just about everyone in the record industry.

Elliot Mazer: Janet was a good engineer and a very cool designer. They made a wonderful 3 band parametric eq and many other great innovations.

Shadowplays: One of the artists you brought to Quad was the enigmatic Jake Holmes. What a skewed career he’s had — from a comedy trio with Joan Rivers, to playing the coffee houses with Tim Rose and the Thorns, to penning one of the premier psychedelic anthems, “Dazed and Confused”, to ending up finally as one of the most successful commercial jingle writers.

Elliot Mazer: Jake was an interesting artist. I met Teddy Irwin through him. Teddy is an amazing guitarist. He played on a lot of the records I produced including Heart Of Gold.

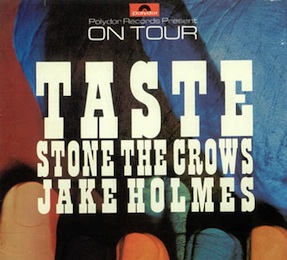

Shadowplays: Teddy Irwin also played rhythm guitar on several of Roy Buchanan albums, another great guitarist that seems to have been all but forgotten. In 1970 Jake Holmes supported TASTE with Rory Gallagher and Stone The Crows on Polydor’s first ever tour promotion. Polydor was presumably attempting to cash in on Taste’s recent explosive performance at the ’70 Isle of Wight. Was it around this time period that you first met Rory Gallagher?

Elliot Mazer: Yes, I met Rory on that tour and was thrilled watching him slay audiences every night. We spent time after the shows talking about music. He loved American music and was interested to hear about my experiences with The Band, Bob Dylan and the Nashville scene.

Shadowplays: Speaking of Bob Dylan, you had previously been in the UK for the ’69 Isle of Wight show, recording Bob Dylan’s return to the stage. Was the complete recording ever released?

Elliot Mazer: Bob Dylan and The Band at Isle Of Wight was a mess. Bob and The Band were at odds with each other. Bob does not like to rehearse and the few rehearsals we had were not very productive. The Band had made Music From Big Pink and they did not see themselves as Bob’s backup band. One track came out on Self Portrait. That was a funny gig. Bob had commanded a huge amount of money for the gig. The Who were scheduled to play that afternoon. During a set change, a helicopter hovered over the back stage area. The Who were in it and their manager was arguing with the promoters about getting them more money before they landed. They did play. George Harrison with Pattie Boyd and John Lennon with Yoko were at the gig and they stayed at the estate we were stationed at. Jagger and Keith Richards were there too. George was interested in Big Pink. They had just finished Get Back and they were curious that both bands came up with similar laid-back feels around the same time.

Shadowplays: After the ’70 Isle of Wight, Taste seemed destined for stardom but broke up soon after the following Polydor tour. Many Rory Gallagher fans wonder how successful Rory could have been if he had remained in that group. After the Eddie Kennedy debacle and the acrimonious breakup of Taste, I think Rory never really trusted anyone else to manage his career and that seemed to include the producing of his albums. Do you remember your conversations with Rory on that tour? What did you talk about? What was your impression of him?

Elliot Mazer: I remember really liking him and mostly only talking about music and musicians.

Shadowplays: That ’70 Polydor tour with Taste and Jake Holmes also had Stone the Crows (with Maggie Bell) in support. Several years later their guitarist Les Harvey would die during warm-up for a concert in Wales, electrocuted from an improperly grounded microphone. This episode led to your development of D-zap, didn’t it? Can you tell me a little about D-Zap and how it worked?

Elliot Mazer: Yes, that is correct. D-Zap was a small device with a jack for a guitar cord one on end and a probe on the other. You plugged the cord that was plugged into your amp or pedal. You touched the probe on your mike and any others you may touch. If the LEDS light up, back up and call the stage manager.

Shadowplays: After the death of Les Harvey, Stone the Crows, tried to carry on, but it didn’t last. One of the more poignant moments of the ’72 Great Western Festival was Maggie Bell dedicating “Fool on the Hill” to Les, just a few weeks after his death. Steve Howe from Yes had stepped in to take Les’ spot for the show. Rory Gallagher headlined that festival and played on consecutive nights due to a cancellation by Helen Reddy. Typical Rory — play anywhere, anytime!

This ends Part One of the interview. Part two will cover Elliot’s work at his studio in San Francisco, His Master’s Wheels, and his work with Rory Gallagher.