Aug 05 2015

TIMELESS — Trevor Hodgett remembers Rory Gallagher

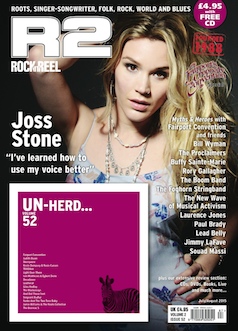

In the latest edition of R2 Magazine (previously known as Rock’n’Reel), there is a 3 page article on Rory Gallagher titled, “TIMELESS — Trevor Hodgett remembers Rory Gallagher”, with some interesting quotes from John Wilson, Gary Moore, Billy McCoy from the old Belfast group “Just Five”, and Billy Boy Miskimmin from Nine Below Zero and Yardbirds. Trevor Hodgett is a freelance music journalist, and co-wrote with Colin Harper the book Irish Folk, Trad & Blues: A Secret History; indeed, some of the quotes from Taste’s John Wilson found in this latest article are from that book. Sean McGhee, editor of R2 magazine has graciously allowed us to post this article on Shadowplays. Thanks Sean! Be sure to check out R2 magazines presence on the web at:

TIMELESS — Trevor Hodgett remembers Rory Gallagher

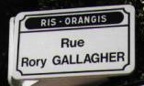

There are streets or plazas named after him in Paris, Cork and Dublin; there are theatres named after him in Ballyshannon and Cork; there are, variously, statues,sculptures and plaques commemorating him in Belfast, Dublin and, again, Ballyshannon and Cork; there is an Irish stamp depicting him; and there are annual festivals in his honour in Japan, Holland, Germany, Norway, Greece and Ireland.

And yet Rory Gallagher, in a recording career that began with Taste in the late 60s and lasted until his death in 1995, never had a hit single in the UK or America, only had one Top Ten album in the UK and none at all in America, and spent most of his career playing modestly-sized theatres, concert halls and clubs.

So how did a musician who commercially had an unexceptional career, who didn’t have big-selling records and who didn’t draw huge crowds, move people to the extent that there are few rock musicians who have had more memorials created in their honour or who are remembered with as much love?

Joe Bonamassa, speaking to this writer in 2008, captured the essence of Gallagher’s appeal: “When I listen to his music I hear a guy doing it for the right reasons. He had no pretense, he was just a guitar player and he loved the blues and he loved rock and he loved to entertain. There was no put-together show, it was just like he walked up there dressed like everybody in the audience and just killed it and walked off and would have a beer with anybody and talk to anybody. Those are things I could relate to – I grew up with people around me looking and acting like that so that’s why I love Rory Gallagher.”

Gallagher was born in Ballyshannon in the Irish Republic in 1948 but spent most of his childhood in Cork. He became a professional musician in 1963 with The Fontana showband, who later changed their name to The Impact, playing the Irish ballroom circuit but also in Germany, England and Spain. “One night I heard Muddy Waters on the radio and it changed my life,” he once said. Forming Taste with Eric Kitteringham (bass) and Norman D’Amery (drums) enabled him to concentrate on the blues he loved.

When Just Five, a band from Belfast, the Irish city with the strongest blues scene, arrived in Cork for a gig minus guitarist Tiger Taylor, a local recommended Gallagher as a dep. The liaison proved significant for Gallagher. “He played guitar and harmonica with us and the band went down great,” recalls Just Five’s other guitarist Billy McCoy. “I asked him did he fancy coming to Belfast and joining the band but he said he was committed to Taste.” Soon, however, Taste themselves moved to Belfast and Gallagher arrived unannounced at McCoy’s door. “He stayed four months – and my mother and sisters wanted to throw me out and keep him because he didn’t drink or smoke and he was really polite and well-brought up and a really nice guy,” laughs

McCoy.

Taste became regulars in Belfast venues like Club Rado and Betty Staff’s. “Rory had the ability to take a song and make it his own,” recalls McCoy. “But it was more him as a person I liked. He was a sound dude, man.” Extraordinarily, another future guitar legend, Gary Moore, who, like Gallagher, died prematurely, in 2011, was also active on the Belfast scene at the same time. “We did loads of gigs together at the Club Rado,” he told me in 2008. “I was only a kid and he was the nicest guy in the world. I really did look up to him. I loved how he played and how graceful he was on stage. He really had the whole thing down. He was brilliant.” Taste were now managed by Eddie Kennedy who, in what many saw as a Machiavellian, divide-and-rule manoeuvre, replaced Kitteringham and D’Amery with local musicians John Wilson (drums) and Richard ‘Charlie’ McCracken (bass). Wilson and McCracken were, nevertheless, undoubtedly phenomenal players.

“The music would have been blues-based but there was lots of improvising and Rory’s inventiveness was endless,” Wilson enthuses of the new Taste.

He was, however, dissatisfied with their studio albums, Taste (1969) and On The Boards (1970). “There was never any thought put into them,” he sighs. “It was straight in and straight out. No overdubbing or nothing.”

Gallagher, an Ornette Coleman fan, occasionally doubled on alto sax. “There’s a fearlessness a lot of Irish musicians have so, yeah, there were gigs where he produced the alto much to the amazement of the masses,” says Wilson.

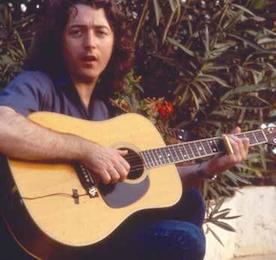

Photo from Defender album cover shoot – 1987

Wilson remembers Gallagher’s abstemiousness: “Rory did virtually no drinking at all – maybe just the odd beer. Drugs? No, no. All Rory was into was playing and writing and exploring all kinds of music. He would have spent a lot of time on his own. He wasn’t a recluse; he just liked doing his own thing.”

Billy McCoy uses virtually the same phrase of Gallagher: “He just did his own thing. I don’t know why he never had any serious relationships with females but that was just Rory. He was incredibly shy.”

Tensions began to emerge in Taste that divided the band. “Rory realised that something did not smell right [financially],” recalls Wilson, “but Charlie and me couldn’t believe that [our manager], somebody from Belfast, could do that sort of thing.”

A feature of Taste’s gigs was Gallagher, mid-song, standing beside one or other of his colleagues, ostentatiously exhorting them to ever-greater intensity. With bad feeling over the band’s finances poisoning relationships, an irritated Wilson once lashed out with a drum stick, breaking, according to legend, Gallagher’s strings. “Well, I wouldn’t have broken any strings but the guitar may have gone out of tune,” concedes Wilson. “Which meant that Charlie and me would have had to play on our own!”

The band, seemingly on the verge of superstardom, broke up acrimoniously. “That nearly finished Rory,” says his brother Donal, Taste’s roadie. “He could have come out of Taste and hung his guitar up. Depression set in that it had all gone so horribly wrong.”

Donal found himself, incrementally, taking over management responsibilities which he then carried out for the rest of Rory’s career. As a solo artist Gallagher initially thrived with a backing band in which bassist Gerry McAvoy featured for twenty years.

“Even though he was playing blues you could hear some Irish-ness within that and he created his own style,” declares McAvoy. “He was a fantastic musician and an absolute gentleman. But he was very insular, a loner. He liked his own time.”

In the 70s, the bloodiest years of the Troubles, when many artists refused to play in Belfast, Gallagher’s regular visits were thrilling events. Bill Miskimmin, who later played harmonica with Nine Below Zero and The Yardbirds, remembers Gallagher’s Belfast gigs vividly: “I saw him many times in the Ulster Hall. I remember the anticipation and everybody dressed like Rory in checked shirts and jeans, with long hair

“The music was absolutely brilliant and the atmosphere was crazy. There were so many people the floor would be undulating – it actually gave in one time. Fabulous, fabulous, fabulous concerts.”

Arguably Gallagher’s music became less adventurous after Taste but his fans lapped up albums like Blueprint and Tattoo (both 1973). His music did move away from blues, however, and albums such as Photo-finish (1978) had more of a hard rock sound.

But by the mid-80s, Gallagher, unexpectedly, had begun to falter, suffering from assorted phobias and neuroses. He had also, belatedly, begun drinking heavily

His old Belfast pal Billy McCoy noticed the change. “The last time he played the Ulster Hall I went to

the dressing room,” he says. “He was pacing up and down and he never spoke to me and I says, ‘Hey, boy, what’s wrong?’ And he says, ‘I always get really nervous before I go on.’

“We went back to the Europa Hotel that night. He had hit the bottle by then and we drank until four in the morning. [Before] he would have sat with a Coke.”

Donal denies that alcohol was Rory’s downfall: “He had problems, like he was a very nervous flier and he was on medication to calm him down. And the medication built up considerably and made a very active person, mentally and physically, draw back. He certainly had a drink

problem but medication was the poison that damaged his liver.”

Latterly Gallagher lived in a hotel, rather than in his own home, which seems sad. “I felt he was a lonely person,” explains Donal. “He was used to touring and hotel life and he wasn’t domesticated whatsoever, as regards simple things like laundry or eating and cooking, so I thought maybe the best situation for him was a hotel.”

Donal believes also that Gallagher’s failure to achieve the success his musicianship deserved disillusioned him: “He was popular but the record company weren’t getting the record sales up to match and he felt the effort he was putting in wasn’t being seen.

“I remember him going through his teenage years, completely obsessed, blanking out any interaction with friends other than people in the band. And through his twenties it was a complete vocation to him. And then when you’re in your thirties you say, ‘I’ve given it everything and it’s not giving me back, recording-wise at any rate, the recognition.’”

Gary Moore also witnessed Rory’s disillusionment. “Poor old Rory,” he sighed when we spoke in 2008. “He was living in the Conrad Hotel in London and I sat with him in the bar one night and he was drinking pints of Baileys. We sat up half the night and had a nice chat but he was in a bad way. He had eczema on his body and was very stressed out about the music business and upset about the way it had all gone.”

With Rory’s health and mental state ever more precarious Donal felt he was better off touring. “When he was off the road he was an absolute disaster,” he says. “He didn’t have a family around him and he couldn’t cope on his own. But on the road I could keep an eye on what he was eating and drinking.”

Rory was evidently so obsessed with music that it’s hard to imagine him indulging in the normal social niceties like chatting about family or remembering people’s birthdays. Donal agrees: “Yeah, absolutely. Anything in the arts – cinema, theatre, writers – you could discuss with Rory. And politics. He was extremely well-read. He’d get a few newspapers every day and in America, no matter what State you were in, he’d know the name of the Governor, the party in power, what the dirty laundry was.

“But I don’t know that you’d have personal conversations with him. I mean, we’d have conversations about my mother’s well-being. Would she be better off living closer to us? And he’d go, ‘I’ll leave that to you.’”

Having said that, Donal then laughingly remembers seeing another side of his brother when Bob Dylan visited Rory in his dressing room at the 1994 Montreux Festival: “The whole conversation was about Dylan’s kids! Rory knew what they were all up to. And I thought, ‘Hang on, this is a conversation you should be having with me.’”

Donal recalls how demanding Rory was: “He’d ring at two in the morning and say, ‘Do you fancy going to eat?’

“And he didn’t like anything too structured. You’d say, ‘We need to book an American tour,’ and he’d say, ‘Oh, don’t even tell me.’ And then he’d hold you to ransom. A week from the tour he’d say, ‘Well I never said I’d do it.’”

Rory died on 14 June 1995, aged forty-seven, from complications following a liver transplant. Many of his peers were devastated. Jack Bruce, for one, said to me soon afterwards, “It really got to me when Rory died. That was a great loss. Just very sad. I don’t know what happened because at one time he was spoken of in the same breath as the greats and he deserved to be, but for whatever reason he went out of the public eye a bit.”

Rory & Jack Bruce at the Rockpalast in Cologne, Germany in 1990

Since his brother’s death, Donal has managed Rory’s legacy diligently. Initially various of his albums were reissued with Tony Arnold remixes. More recently they have been remastered by Donal’s son Daniel Gallagher, using the original mixes, and reissued again.

And new Gallagher albums have been created including the acoustic Wheels Within Wheels and Notes From San Francisco, a remixed version of an album that Rory had recorded in 1977/’78 and then rejected.

Donal still winces recalling Rory vetoing the original album: “We were in Los Angeles and Chrysalis had brought in representatives from every State. I went to Rory’s room [for] the acetate to play for these guys and he said, ‘No, I’m not happy with it.’

“I said, ‘Look, I’ve got to face these executives,’ and lifted the acetate and he pulled it out of my hand and binned it.

“And I remember getting really angry. I said, ‘These people are going to barbecue me. I’m so angry I could break your leg.’ And I stormed out and had to go and talk my way out of that one.”

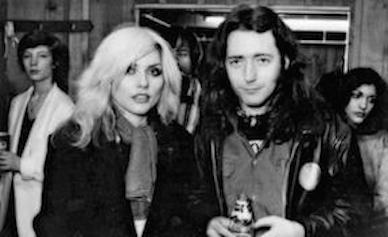

The album had been recorded in San Francisco and seeing The Sex Pistols at the Winterland on a night off had influenced Rory. “Rory got off on the ethos of punk,” says Donal. “It was about getting on stage and letting rip, the ethos of rock’n’roll itself.

“So he went out of curiosity, and later he said, ‘I don’t know whether it was one of the best gigs or worst gigs I’ve ever seen!’ But it certainly gave him a thrill.

“And he then had a desire to switch back to keeping [his music] simple and rocking. In the studio [producer] Elliot Mazer had had him layering guitars, which wasn’t entirely Rory’s thing, so when we went back to the album we dispensed with a lot of the layers of guitar.”

Gallagher’s music has stood the test of time. It has been admired for decades not only by legions of fans but also by his rock star peers. But it is desperately troubling that a man who made so many others happy, who was seemingly liked by all who knew him, apparently couldn’t find happiness himself, could find so little meaning, so little to satisfy him, offstage.

Guitarist Andy Powell, of contemporaries Wishbone Ash, offers an insightful perspective on Gallagher’s sad demise: “Sometimes musicians mortgage everything in life to music and Rory was one of those guys. You do have to be passionate, you do have to be single-minded but you do need to live as well. You do need to open yourself to life. Then you’ll get longevity.”

- Some John Wilson quotes here are from Irish Folk, Trad & Blues: A Secret History by Colin Harper and Trevor Hodgett.

- Photos of Rory in the article provided by Donal Gallagher, Rory’s brother and road manager

Thanks for this. So happy to see a renewed interest in Rory, both in the music press and among listeners.

Great article!

Such a talented & beautiful man. There is a song on ‘Jesus Christ, Superstar’ that absolutely reminds me of RORY. A gorgeous song penned ‘Pilate’s Dream’. It breaks me up when l hear it. ? l play in a RORY tribute band in Australia. My dream would be to play his guitar at his yearly festival. Difference being, l’m a woman. I don’t sing or play the harp; the rest of the band are guys. But l’m the only guitarist. I have my 63Lseries STRAT, & a 1932 Dobro. RORY has been my mentor since l was 8 years old. lt would absolutely be my life’s dream to do this for RORY, not myself. I seek no fame or money. I honestly HOPE DÓNAL would consider this. To say ‘THANK YOU’ to RORY & DONAL. Donal certainly had his hands full, l appreciate his efforts. Sincerely Belinda ?

I fully understand why Rory didn’t want the San Francisco album released. I bought it and never play it, it just isn’t Rory.