Jun 24 2015

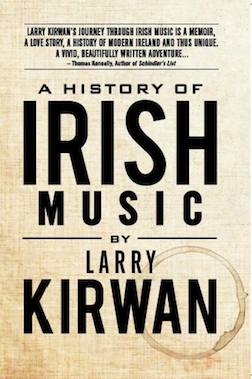

A History of Irish Music by Larry Kirwan — Chapter 9

Larry Kirwan, is an expatriate Irishman from County Wexford who has made New York his home for the past 30 years. Leader of the recently disbanded Celtic Punk band Black 47, a mainstay in the New York City music scene, Larry hosts his show ‘Celtic Crush’ on Sirius radio, and writes a weekly column for the Irish Echo. He is a prolific writer of plays, musicals, and books, including the highly regarded Green Suede Shoes. His latest offering, A History of Irish Music is a must reading for anyone interested in Irish music culture.

“From Wexford town to New York, from folk to punk/new wave, from the fervour of youth to the consideration of maturity, from politics to polemics, Larry Kirwan invests his subjective view of Irish music with a keen eye for detail and a deft turn of phrase.” — Tony Clayton-Lea Irish Times music critic

Of particular interest is Larry’s chapter devoted to Irish legendary guitarist and singer Rory Gallagher. Larry has kindly allowed the posting of this chapter on my blog. Thanks Larry! You can purchase the book on Black47.com, Amazon, and other major outlets.

A History of Irish Music by Larry Kirwan — Chapter 9

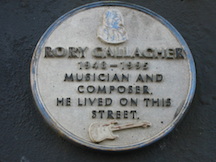

Let’s leave Donal Lunny for a while – never an easy task when dealing with Irish music – but I want to backtrack and deal with someone who’s rarely considered a Celtic artist yet is fundamental to any understanding of modern Ireland and the music that has sprung from it. He was born in Ballyshannon in County Donegal but moved to Cork City in his early years. He may have been the most thrilling guitarist I’ve ever seen – he was definitely the most consistent and passionate. His name was Rory Gallagher.

Rory

Hey Rory, you’re off to London

Playin’ the blues with a band called Taste

Gonna hit the big time?

You better – you’re the best

On your night you could even leave

Hendrix in the dust

I want to thank you for what you did

No more messin’ with the Kid

Hero came back to Dublin

The only one sober we’re all out of our heads

Long hair flyin’

Blue denims drippin’ with sweat

Volts of lightnin’ in your fingers

Pride of bein’ the best

(Larry Kirwan)

Does that song seem bittersweet with a whole dollop of regret, and not a little sorrow wrapped around it? Well, that’s how I feel about Rory when I recall the love and energy he injected into each of his shows. Most of the time, though, when I hear his recordings I just get swept up in the excitement and pride we Irish felt in this force of nature – “old son,” as we fondly called him. When he’d walk offstage dripping in sweat, his long hair streaming down his denim jacket, we’d begin to bawl out to the rafters:

Nice one, Rory, let’s have another one

Of course, we knew he’d be back on stage within minutes playing a number of encores and even upping the ante on the drive, creativity and showmanship that he’d already have doled out over an explosive couple of hours. But there was always the chance that some dumb-ass promoter might not want to pay overtime to his staff and bring the house lights up. If that happened we’d know full well that our hero would never play there again, for Rory Gallagher never allowed anyone to get in the way of the three-way bond between himself, his music and his audience.

Rory was another showband alumnus – his was The Fontana, Van’s The Monarchs; though showbands provided a great grounding in music, the key was to jump ship before you became stuck in their inevitably soul destroying, imitative groove.

My friend, the musicologist Jack O’Leary, once a sailor on British Rail Ferries between Ireland and the UK, recalls Rory and Taste departing Cork for London in 1968 to take a shot at the big time. The young band was pretty much unknown in Ireland. I was already a fan though I’d never heard Taste – my closest association was gazing in awe at a signed picture of the band in a Cork City chipper.

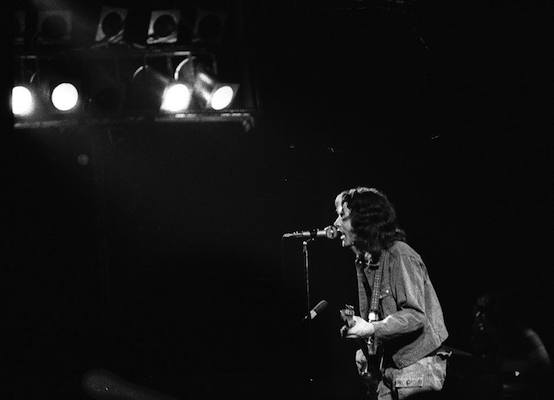

It didn’t take long for Taste to get notice in guitar-crazy London where the big three were Clapton, Beck and Page. Initially what made Rory stand out was his work ethic. The man just loved to play. He’s sold 30 million albums now, but stick to his live CDS; I don’t believe he was ever really captured at this best in the studio – that puts him in the revered company of Marley, Springsteen, and many other great performers. Apparently, while recording he was self-doubting, over-meticulous and a second-guesser non-paralleled. But onstage, he was a force of nature, living totally in the moment and, to my mind anyway, bolts of lightning did flow through his fingers. It was as if he was fighting for his life the minute he strode across that stage and tuned up.

Then again, I was such a fan, his tuning up sounded good to me! But his voice too set him apart from the big three. Rory could sing the hell out of anything – particularly if the tune had some connection to the Blues. His singing was raucous, pleading, passionate and strident, and yet there was tenderness behind it, a link to his own self-doubt, perhaps. Like all the really great performers he was touched either by some divine spirit or something fierce and feral within himself. It would have been hard not to get swept up in the torrent of inspired notes and cries that he unleashed from the stage. Talk about breaking down the fourth wall – Rory vaporized it. I brought many people to see him over the years, some were skeptical on the way in – all were converted and dazed on the way out. Only a supremely ironic and detached individual could resist what that man let loose at audiences. I’m sure there were some such souls, but I never met any.

Rory performing Bullfrog Blues on the French “Chorus” show in 1980

He once approached me in the Television Club in Dublin. He had won some award that night but yet had no assistant, entourage or anything of the like. It had to be the early 1970’s. I was slouching against a wall, shy and unsure of myself in the midst of all the celebration. I thought I might be hallucinating for suddenly he was heading straight towards me in his own shy off-stage manner. He must have mistaken me for some red haired guy from his hometown for he nodded kindly and asked me if he could cadge a lift back to Cork. I was so dumbfounded I didn’t know what to say. Whereupon he apologized and said, “Ah, you’re probably not going home, right?”

“No,” said I, “I’m not,” as he turned away, though I felt like running outside, hijacking a car, and driving him to the city on the Lee, just to give a little something back for all the joy he’d given me.

You see Rory was our first homegrown international star. He was like one of the lads – you could never accuse Van of that. Besides, Mr. Morrison was from Northern Ireland. Many people from the Republic were beginning to learn a lot more about the North than they wished. Van hadn’t a sectarian bone in his body but, though undoubtedly Irish, he had grown up in a very different culture. Rory was one of us, and we took enormous pride in him. We didn’t have a whole lot else; our national soccer team was a joke and the rest of the world didn’t play hurling, but now we had a guitarist/vocalist who could take on the best: “On your night you could even leave Hendrix in the dust.”

We did have Joyce and Yeats, but they’d both been dead a long time; meanwhile up the highway the North was careening from one atrocity to the next. The very centre had caved in big time, and old Willie Yeats’ blood-dimmed tide had well and truly broken its banks. Years of British refusal to deal with overt sectarianism had come home with the chickens to roost. Rory was the one beacon that lifted us above all that, and every Christmas, no matter how bad the political situation, he did a tour of the country that included Belfast. To top it all, everyone turned out; people who wouldn’t walk down the same side of the street together had to rub shoulders as they rushed towards the stage to be closer to the action.

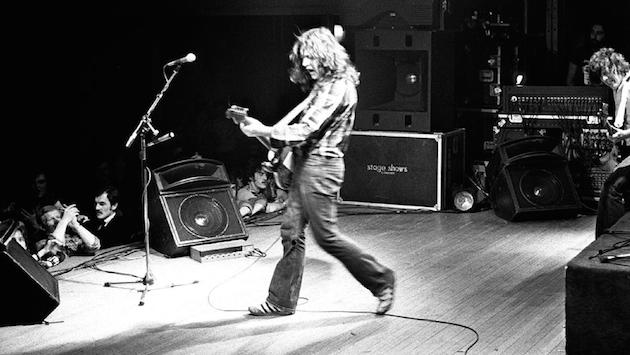

Rory at the Ulster Hall in 1979

He must have known what was going on – must have sensed the danger he was exposing himself to, a lone figure out front of stage soaking up the spotlight. He could scarcely have ignored the British army ringing the Ulster Hall to make sure there were no riots entering or leaving. But Rory was above all that. Music was his god. With the lightning coursing through his fingertips once he hit that stage he didn’t give a goddamn; he was a man possessed and everyone had to suck it up, put aside their politics, preconceptions, hurts, and aspirations. And we did because we wanted to share in the god-given magic that had been bestowed on this slight figure; life was stark enough, who wanted to ruin the few sparks of light that gave us hope in those dark and dangerous days.

Rory looked like us too – he didn’t go in for Hendrix gypsy-vagabond scarves, nor Beck’s velvet or Page’s spandex. No, he wore denim jackets and jeans, plaid shirts and sneakers or work boots in the winter. And, man, did that guy sweat? His very Stratocaster was streaked permanently with the buckets of perspiration that poured off him. And when he sang Blind Boy Fuller’s Pistol Slapper Blues:

When you were stretched out on my bed

Drinking moonshine whiskey

And talking’ all out of your head…

Those were the type of women we had in mind for ourselves when we’d finally get to some Mississippi of the soul that we’d always promised ourselves.

Rory seemed to be the only one not out of his head on booze during those shows. The drinking would come later. His brother, Dónal, once told me that Rory would have been better off if he’d started young like the rest of us – would have learned to deal with the condition earlier. There was one show at the National Boxing Stadium in Dublin when our collective alcohol fumes could have made a small nation tipsy – no booze was sold inside the hall so you had to fortify yourself for two plus hours of abstention before entering. I can’t remember the name of the song, but one audience member was so moved he shimmied up a pole onto a narrow beam and began to edge his way unsteadily over to the stage.

Rory was in the midst of a long solo and was the only person in the hall unaware of this lunatic escapade. The bouncers looked on in amazement – for once none of them willing to follow the perpetrator and kick the shit out of him. Eventually, when the aerialist realized he stood a better chance of joining Rory by rushing the stage, he shimmied on back down another pole and was positively dumbfounded to be turfed out on his arse. That was the effect this Cork guitar slinger had on his audience.

Rory at Dublin National Stadium in 1978

Although Rory was known more for his Stratocaster playing, he was a stunning acoustic guitarist and mandolin player. The Blues with its basic honesty of expression was Rory’s foundation, yet you could feel him edging towards Irish traditional music. He often spoke of his interest in the genre in interviews and he became good friends with Ronnie Drew of the Dubliners. There are videos of his last European tour in 1994 when he plays a riveting version of She Moves =Through The Fair. You can tell he had a great appreciation for the playing of Bert Jansch and Davey Graham. Perhaps even more revealing is his rendition of the old tune Dan O’Hara as you feel him meld the Irish Trad influence with a Lead Belly swing.

It makes you wonder where Rory would have ended up musically. It’s not outside the bounds of possibility that he would have tackled some of the compositions of another Cork blow-in, Sean Ó Riada, and worked his considerable magic on them. Regardless of all his rock and blues influences, I’ve always considered Rory a Celtic musician – even a Celtic warrior in ways, for he took all the passion and melancholy of the irish psyche and wove it into his music, and left behind a testament of what one man with a huge should can achieve with a guitar.

Rory’s sudden death was like a kick in the head. I had heard rumors about his drinking and it was obvious that he had gained a lot of weight. I suppose all this makes sense now; overmedication and an ease of access to prescription drugs are a large part of our culture (if you don’t believe me, take a look in your medicine cabinet). All that aside, it just didn’t make sense to me – Rory was always the clean one while the rest of us were out of our skulls. It ust didn’t seem fair. I had also missed his last show in New York. I was on the road with Black47. I had never missed a local one before. Now there would be no more shows – no more moments when I’d soar to the seat-stained strings of Rory’s guitar. It was like a curtain closing behind me.

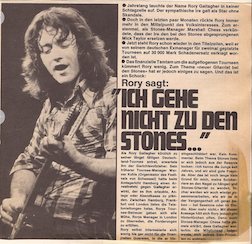

Like many, I was outraged by the showbiz banality of the obituaries in the American press. Their main point seemed to be that Rory had missed his chance – The Rolling Stones had considered him as a replacement for Mick Taylor, but Rory had either turned down the gig or hadn’t passed Mick’s muster. You gotta be kidding me! The Stones missed Rory way more than he ever missed them. He would never have allowed them to turn into a self-referential tribute band, and don’t get me wrong, I love the Stones and pretty much every song in their pre-1979 back catalogue. But what a difference Rory would have made to this great band. He could have single-handedly revived their creative spark. Imagine Keef trying to keep up with this bluesy dynamo? What a power duo they would have made. Talk about intertwining rhythm and lead lines – they were born for each other.

And think of the effect he would have had on Jagger – they could have reinvented the Blues together. But Rory knew better than to join. He wasn’t the type to be nailed to the floor in someone else’s tradition. Nah, he was on a different mission. He knew what he was after and those of us who were lucky enough to be uplifted by his presence at one of his thousands of gigs count ourselves blessed. How often do you get to see streaks of lightning shooting out of someone’s fingertips? In the end, it was like losing a real close friend: you’re left with the memories and the ultimate question, what if?

Where did the lightnin’ go?

Did it burn right through your fingers

To the cockles of your soul?

Leavin’ you stranded

A million miles away from the rest of us …

I want to thank you for what you did

No more messin’ with the Kid

So long, old son, that’s it

No more messin’ with the kid

(Larry Kirwan)

Larry Kirwan reads an excerpt about Rory Gallagher from Victor Zimet on Vimeo.

You can purchase Larry Kirwan’s A History of Irish Music on his website – Black47.com, or Amazon.com, or any number of major outlets.