Jan 10 2015

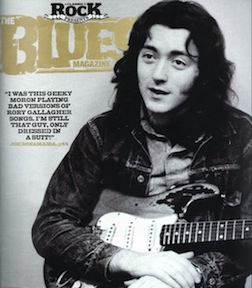

Rory Gallagher’s Irish Tour de Force

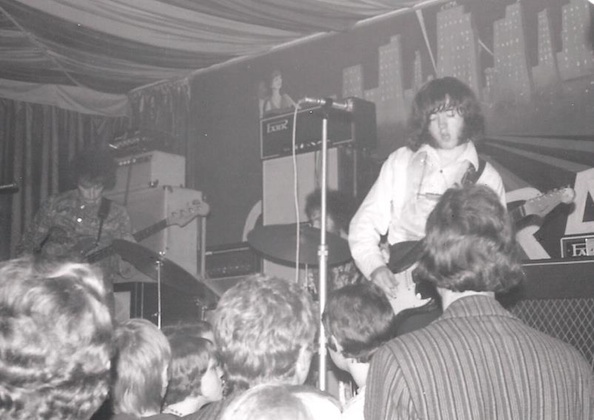

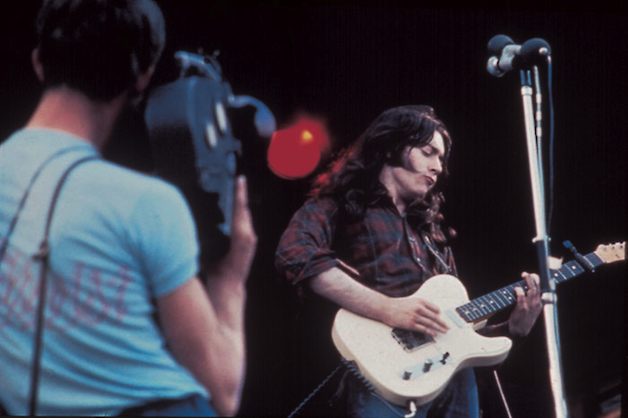

Some albums are so powerful an experience that they forever change the way you look at music. And for me there was no bigger game changer than in 1974 when Rory Gallagher’s album Irish Tour ’74 was released. Not that I wasn’t a fan of Rory Gallagher’s music already, I had previously enjoyed his earlier solo releases such as Tattoo, Deuce, and his eponymous titled first album. But what changed for me that day was my attitude towards “live” albums.

Back then I thought any “live” rock album was just a mess of muffed notes, bad mixes, and way too much hand-clapping; destined for the record store cut-out section. I’d listen for that perfect solo memorized from the studio cut and mid way through the fellow would jig right where he should’ve jagged left, and I’d cry out, “Noooo!”. Live albums were just a way for a band to muddle their way through a 5-album record deal, right?

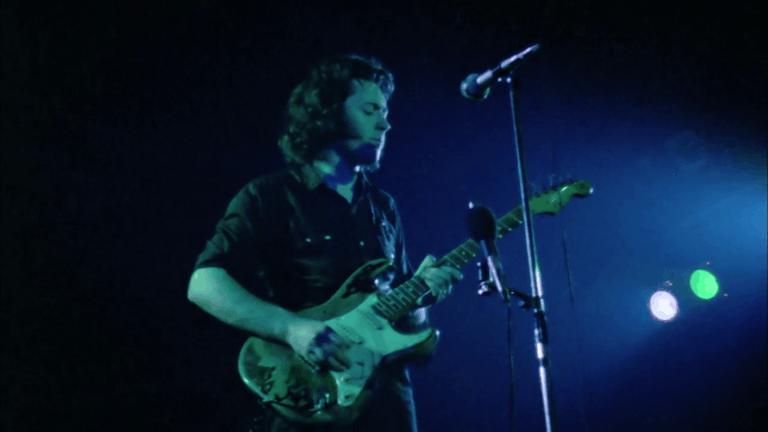

But then I listened to Rory Gallagher’s Irish Tour ’74 and it all made sense. With Rory, the studio album was just a launchpad, a jumping off point to what that song could be once fired in the crucible of a live performance. The live album was about the fulfillment of an idea. It was about the energy,the feeling, the power. God almighty, it was about the power! The power of Rory’s Strat could knock you back a country mile, like a lightening bolt slamming into your chest!

And it was about the ride, the long roller-coaster of a ride that Rory took you on, never knowing exactly where he was going or where he was going to end up, but always glad you came along for the ride. 40 years later, Rory is still taking me on those long incredible journeys. And Irish Tour ’74 is still the benchmark that I measure all other live albums against. I listen to a lot of live albums nowadays, and not just Rory’s, but it’s Rory’s live stuff that I always come back too. Rory showed me the way.

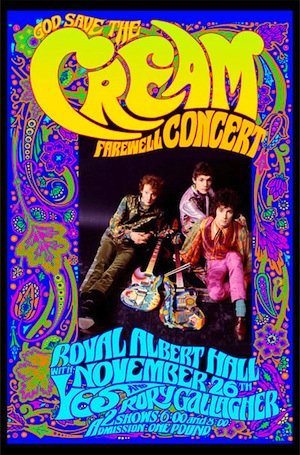

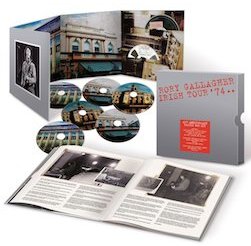

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of this incredible album, Dònal and Daniel Gallagher, brother and nephew to the guitar genius , have released an expanded deluxe edition of that incredible album, including the complete recordings from all three Irish Tour venues: Belfast’s Ulster Hall, Dublin’s Carlton Cinema, and Cork’s City Hall. Because of technical difficulties the original IT ’74 album was largely the live recordings from the final venue in that tour, Cork City Hall. Now, for the very first time we get to hear Rory’s entire Irish tour; all three venues, plus even more material from an after hours “session” that we got a wee taste of on side 4 of the original IT album. The following is a recent interview I did with Daniel Gallagher about the making of this deluxe edition:

The Making of the IT ’74 Deluxe Edition

Shadowplays: Hi Daniel, thanks for taking time out from your busy schedule to answer a few questions about this latest release. Can you tell us a little bit about what you were trying to accomplish with this expanded edition? After all, IT ’74 is arguably Rory’s finest hour. Were you a tad nervous “messing with the kid”?

Daniel Gallagher: Hi Milo, yes I was very nervous. We knew the 40th Anniversary was looming and thought that we had to do something special for this album as for many, myself included, this is Rory at his finest. Which is what made the idea of remixing, remastering or re-ordering the album such a difficult decision, how can you alter something so loved?

Shadowplays: What did you have to work with? Soundboards from the shows mixing consoles , mobile studio 8-tracks? Did you have the audio tapes from Tony Palmer’s IT documentary? His Nagra stereo tapes from all three venues?

Daniel Gallagher: At first I thought there was only the 8 channel, multi track tapes in storage, which held the 2nd Cork show and the city hall jam sessions. So I dug those out and digitised them and started working out the set order and remixing the whole thing. While remixing I started to worry that the new mixes were too polished and were losing the rawness of the original album so we changed tact and decided to mix the previously unreleased songs only and to match them to the sound of the original album. I got in touch with Robin Sylvester to ask how he mixed the original record, what desk he used, what reverbs etc and he kindly thought back 40 years and sent me a good description of what they’d done. My engineer Martin Dubka had also guessed much of it and we set about ‘recreating’ Robin’s mix over the new songs such as ‘Hands Off’, ‘In Your Town’ etc.

Meanwhile I asked Tom O’Driscoll who manages our archive to have a dig through for anything he could find relating to the Irish Tour, anything from tickets to posters, news clipping etc. He found hidden under load of master tapes a wooden box full of Nagra tapes. I went through them and they had random bits of writing on them but after putting them in order it became apparent that it was all the audio recordings from the Irish Tour film. These Nagra reels held the soundboard recordings from all the shows through the tour.

Shadowplays: What condition were these assorted tapes in? Had they deteriorated or been damaged after so many years?

Daniel Gallagher: Amazingly not! The tapes were all in pretty good nick. They get ‘baked’ at the digitising stage to take out any moisture that may have seeped into them, which can make the tape sticky, after this they were all fine. One major problem though was that one of the multi tracks from the Cork concert is missing and this had ‘Laundromat’ on it. We had to use the version on the Nagras in it’s place.

Shadowplays: Obviously the overall sound quality of the Cork City Hall tapes are the best of the lot since they were recorded on 8-track using Ronnie Lane’s mobile studio, but even the mixing console tapes from the Belfast and Cork shows are reasonably clear. Maybe a couple of times, during the Belfast show, Rory’s guitar might have gone missing, buried underneath Rod’s drumming or Lou’s piano playing, but overall you hear how it sounded to the audience, and to me it sounded pretty darn good. How exactly can you change what’s been funneled into the original mix and outputted to the speakers anyway? How does remastering help the sound from a soundboard?

Daniel Gallagher: With the Belfast and Dublin recordings you are restricted as to what improvements can be made. For starters you can’t change the mix in any way so if the guitar is quiet in the original mix from the show you can’t suddenly turn it up. What can be done at mastering is to tweak the EQ to bring out certain frequencies or reduce others, this can help pull out the guitar that might be buried in a mix. At mastering there’ll also be compression and limiting added to the recording to bring it to a more standard audio volume level, which the original tapes aren’t at.

There are moments in those two concerts where for instance Rory’s vocal mic distorts as he shouts the opening lines to Bullfrog Blues or at the start of the Belfast set the guitar is low in the mix and the bass is too loud for the first track but this is exactly what the live mix in the venue was so it’s still pretty cool to hear what the audience heard that night heard.

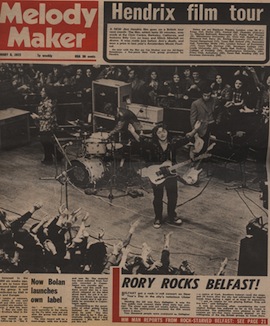

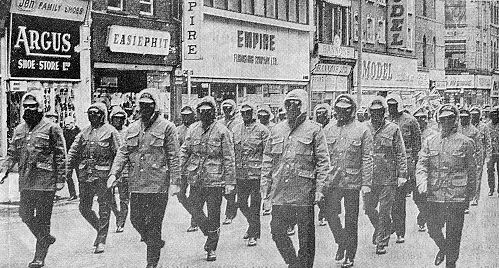

Shadowplays: For me, the highlight of the Belfast show was “Going To My Hometown”. The enthusiasm of the crowd was fantastic. It really shows off Rory’s ability to communicate and bond with the audience. I think too often blues-rock bands put up a wall between themselves and the audience, particularly back then in the late Sixties, early Seventies, but with Rory it was like he was playing directly to you, one-on-one.

Daniel Gallagher: “Going To My Hometown” is such an interesting track in this set because of the different audience reactions / participation to it, across the cities. In Belfast it feels quite spiritual, cathartic for the fans, in Dublin they’re a bit more boisterous and they chant every word. Interestingly it’s the Dublin audience that sing the infamous “Nice one Rory, nice one son, nice one Rory let’s have another one” which actually comes after GTMH as Rory’s switching from Mandolin to guitar. Not to ruin peoples memory of the main album I kept it on the Cork album but moved it to after GTMH in keeping with where the Dublin crowd had chanted it. In Cork, Rory sings an interesting line “Going to my hometown, the Queen of the South, you know what town I’m always talking ‘bout” I definitely think the song is about Cork (“got me a job from Henry Ford” is a reference to the Ford car plant in Cork) and in all the cities you can sense Rory working the song to fit the crowd.

Shadowplays: I love the inclusion of “Just a Little Bit” in Rory’s Bullfrog Blues encore during the Belfast and Dublin gigs. Do we know the reason why there’s no Bullfrog Blues during the Cork show? Or was it just not recorded?

Daniel Gallagher: I thought it was weird when I first got the multi tracks that there wasn’t ‘Bullfrog Blues’ on the tapes and thought maybe they just ran out of tape, but it seems it wasn’t played at either of the Cork shows after I cross checked the Nagra tapes. The only thing I can think of is that they had a strict time limit at the venue, it was the Cork City Hall, and as the set is already over 2 hours. Rory may have been obliged to end his set.

Shadowplays: Looking at the set listings for each of the gigs, one thing immediately stands out as pretty unusual for Rory. Nearly identical track listings. Being a collector of Rory’s live recordings myself, I don’t recall ever seeing Rory do the same set list two days in a row. Was this a concession to Tony Palmer’s documentary needs? I understand he was suppose to dress identical so they could mix and match clips from all 3 venues.

Daniel Gallagher: Yes I think Tony Palmer wanted to be able to cut between the various venues during the same song to show the different audiences across Ireland and their reactions to the music, so he requested that the sets were roughly the same. Though looking at the film Rory didn’t listen to him when it came to wearing the same shirt every night and in true Rory fashion none of the versions of the songs are identical in length or performance.

Shadowplays: In the liner notes, you’ve listed 2 dates Cork shows and 2 dates for the Belfast shows. Did you have to cobble together the track list between the two dates for each venue?

Daniel Gallagher: There were two Cork shows, one on a Thursday and one on a Saturday. The multi track recordings come from the Saturday concert and I used all of that bar Laundromat which comes from the Thursday night as far as I remember. Also I think the original ‘As The Crow Flies’ also comes from the Thursday concert. The Thursday night show Nagras were missing quite a few tracks from the set that’s why I didn’t do another disc with that show. Belfast there was only one night recorded but from Rory’s diary and an interview caught on the film audio there was another concert which was possibly a matinee show.

Shadowplays: Listening to these shows in chronological order (Belfast, Dublin, then Cork) you get a sense of consistency but also variation in Rory’s playing. All three shows are such high energy treats, with incredible playing, and strong voice, but there’s also a lot of variation in his playing, never playing the songs, especially the solos, the same way twice. What’s your favorites from the Dublin and Belfast shows?

Daniel Gallagher: Across all the shows I love when the band starts ‘In Your Town’ straight out of ‘Who’s That Coming’ and Rory tunes his guitar on the fly and joins in with the riff. I can’t think of any guitarists even back then who would do this, anyone else would have a guitar tech handing them a new guitar with the correct tuning for the song. ‘In Your Town’ is such a fun song especially with Rory riffing with the gangsters who are going to join him on his jailbreak.

Dublin was an interesting concert to put together because I felt like I’d heard it before but couldn’t realise how, then it clicked that a lot of the films audio comes from the Dublin concert. As you say it’s great hearing the variations of solos and licks Rory plays in the different versions of songs, ‘Walk On Hot Coals’ and ‘Hands Off’ have so many fantastic differences. The acoustic part of the Dublin concert is great, I love the reception ‘Unmilitary Two-Step’ gets. I think ‘A Million Miles Away’ from Belfast is pretty special, something about Lou’s keys being a bit louder in the mix really work with the vocals and then Rory’s lead lines and licks pop out really nicely. It’s cool to hear Rory sing ‘Just A Little Bit’ during ‘Bullfrog Blues’ as well.

Shadowplays: The Cork show is something special though. Do you think because the Cork show was Rory’s last chance at recording with the Lane mobile that it spurred him on to greater heights? Certainly his back was against the wall and he just manned up and nailed it! Thankfully Ronnie Lanes mobile was set up to record that very special night.

Daniel Gallagher: I can imagine it was a big disappointment for Rory that the Lane Mobile didn’t make it in time to record the other shows as he probably would have loved to have had the different crowd reactions on tape to work with and as Rory always played off the crowds energy he would’ve known what night had the best version of a particular song.

From a purely technical sound aspect it’s possibly fortuitous that the Cork show was the only one properly recorded as all venues have a different sound, the room reverberates differently due to the size, the amount of people crammed in etc. Trying to make three different venues sound like one night would’ve been quite difficult and would’ve involved adding a lot of reverb and other effects after in mixing. The amazing thing when doing the mixes to match Robin Sylvester’s is that of the eight channels (drums L, drum R, bass, piano, guitar, vocal, audience mic, film sync code) the majority of the mix is the room mic. The natural sound of the room with the band playing and the audience clapping, singing along etc is integral to the sound of the album, if you were trying to balance this across the three venues it might have led to a neutralising of the natural atmosphere.

I’m not sure what it is about the Cork night though that just is that touch more special, everything Rory improvises comes off, the way he segues between songs just works whereas on the other nights there might be the odd stumble. Maybe it was just the added pride of playing in his hometown with a highly respected film director filming him, the feeling of coming home and showing everyone that he’d really made it.

Shadowplays: The extra tracks from that Cork show are so good, I’ve got to wonder why at least some of these tracks weren’t included in the original IT ’74 instead of using the After Hours session on side 4. The after hours stuff they did use is good, but to the exclusion of such gems as ‘Hands Off’? Or Going to My Hometown?

Daniel Gallagher: I guess when Rory was compiling the tracks for Irish Tour he probably had in mind that the tracks that featured on Live! In Europe would be left off so Going To My Hometown, Messin’ With The Kid etc were excluded. Hands Off which is, to use the cliche, a tour de force I can only imagine missed the cut because of it’s length. Being geeky about it he could’ve structured it:

Side 1 Cradle Rock, I Wonder Who, Tattoo’d Lady.

Side 2 Walk On Hot Coals, A Million Miles Away

Side 3 Hands Off, Too Much Alcohol

Side 4 As The Crow Flies, Unmilitary Two-Step, Banker Blues, Who’s That Coming

Not sure where the idea to use the After Hours recording instead of live material for side 4 came from, possibly Rory wanted to have his version of ‘Just A Little Bit’ on the album but as they hadn’t played it (with Bullfrog Blues) in Cork they had to go with the jam recording. Back On My Stomping Ground maybe made the album as Rory might’ve wanted to have a new composition of his own on the album, as most of the set, bar covers, is from Tattoo.

Shadowplays: Disc 7, the Cork After Hours recordings, were they done the day prior to the final gig? Checking levels? Running the sound through the mobile? That afternoon session seems a bit more than just checking out the Lane mobile though. It’s not just bits and pieces of songs, but full songs that seem very well polished as well. Was it a bit of a fail safe mechanism then? After all, this was their next to last chance at recording some material with the Lane mobile. Maybe Rory was concerned that they wouldn’t get enough material from the next day’s show?

Daniel Gallagher: It was my guess and Donal’s memory that the City Hall Sessions / After Hours material came from the day before the last gig. We felt if the mobile unit was there prior to that, then it would’ve been used to record the first Cork show so our feeling is that it arrived on the Friday and they set about testing the studio out then. Some of the recordings are very much a sound check such as the acoustic medley and Dylan instrumental, just the band warming up as cables are plugged in, levels checked etc. The full song performances of ‘Treat Her right’ and ‘I Wonder Who’ that are so great might be because they were being filmed by Tony Palmer and Rory thought they might make it in the film, so he was aware of still having to really perform even at soundcheck.

Shadowplays: I didn’t realize that Tony Palmer filmed the recording of these gems. A shame it didn’t make it into the documentary! Filming Rory working out how best to do a song would be a fun thing to watch. The bits and pieces of songs you’ve included in the After Hours session are interesting. Nice to hear a bit more of Maritime. The tune becomes a bit less Shadows and a bit more Rory towards the end, doesn’t it?

Daniel Gallagher: Maritime strikes me as Rory starting something as a bit of a Shadows parody but he then gets caught in the moment of coming up with something new and suddenly you can hear him playing a bit more seriously.

Shadowplays: And the short bit of Dylan’s ‘I Want You’ that Rory plays during the Cork session was beautiful, makes me wonder if he ever had ideas of including a Dylan cover on one of his albums. In later years he’d play a few Dylan tunes during his show; such as, ‘Don’t Think Twice,’ ‘Just Like A Woman,’ and even ‘Highway 61 Revisited’!

Daniel Gallagher: I think I read somewhere that in the early Taste days they used to cover “Don’t Think Twice”, Bob Dylan was definitely Rory’s favourite artist, he references him so often and seems to have really followed and studied all of Dylans work. Of anyone he could’ve played with or alongside I’m sure Dylan would’ve been Rory’s number one choice.

Shadowplays: And then there’s the playfulness of Rory’s playing in the Bill Justis tune, “Raunchy”, the exaggerated bending of the notes.

Daniel Gallagher: To be honest I didn’t know the tune “Raunchy” and was trying to give the track a title till my Dad recognised it. It’s got a cool laid back riff and I love the rockabilly muted chord arpeggios that Rory plays in this and actually in quite a bit of the album

Shadowplays: It’s nice to see both Stompin’ Ground version on the disc. It’s interesting to see the evolution of that song. Surprised the tune didn’t show up on Against the Grain. Same with the other complete songs from the After Hours sessions, though some were eventually used as CD bonus tracks.

Daniel Gallagher: I think Rory might have been taking advantage of having the mobile unit spare on that day to put some new ideas down as the two versions of Stomping Ground have overdubbed vocals in certain places so I imagine Rory hadn’t finished writing the track and was trying out different ways to play it with the band. When he was mixing the album he recorded the new lines and added it to the track, that’s why there’s a weird slapback type sound to the vocals in certain places as the vocal overdubs were done on the room mic channel so sometimes double the vocal. Just to reassure there aren’t any overdubs on any of the live material!

Shadowplays: Not always true with some other famous “live” albums, the Band’s “Last Waltz” immediately comes to mind, but with Rory what you hear on IT ’74 is how it sounded during the show. So is there anything else that wasn’t included in this deluxe edition? Any more bits and pieces of songs from the afternoon session? The “end of tour” party? I heard mention of an interview? Tony Palmer doesn’t have any footage lying around collecting dust, does he?

Daniel Gallagher: I’ve edited together Rory’s guitar and music talk with Tony Palmer from the soundcheck which in the film is only a few minutes but runs to about 20 minutes in total. I couldn’t get Sony to let me include it in the package on a ten inch vinyl, in fairness 8 discs is quite a lot. I’ll try and find another way of getting this out.

There was some bits of recording from the Cork Boat House after party and a few minutes of the Dubliners with Rory in the bar at the Gresham Hotel in Dublin but sadly nothing really usable as a complete song as there is so much background noise of people talking, pint glasses clinking etc.

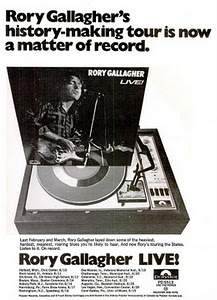

Shadowplays: With the deluxe version of Irish Tour ’74 in the can, is there a possibility of doing a deluxe version of LIE? Do you still have the recordings made from the Pye Mobile? Robin mentioned 3 English shows that were possibly recorded using the Pye mobile: Luton, Nottingham(Birmingham?), and Leicester. He also mentioned the Gerhard Henjes tapes from Germany and Holland.

Daniel Gallagher: I’d love to give Live In Europe the same treatment but as yet I haven’t come across tapes of the other shows.

Shadowplays: Hopefully those tapes resurface!

Considering that LIE was taken mostly from one show, the Luton Town Hall gig and IT ’74 was mostly from Cork City Hall, I wonder whether the cohesiveness and balance that a single concert produces was perhaps the missing piece for the StageStruck Live album, still a great album, but perhaps it would have been even better if it had come from a single show.

Daniel Gallagher: With Stagestruck you can hear the heavy use of reverb to cover the sound changes of the different venues and, for me, that’s why it isn’t as strong a live album as the other two. Of that era I think the Notes From San Francisco live disc gives a really good impression of what the much heavier and louder three piece line up with Ted and Gerry was like.

Shadowplays: The Pye mobile unit not only recorded the shows for Live In Europe, it was also used for the 1970 Isle of Wight recordings. I understand you are now at work with the Taste material. Are you looking to do an expanded Taste Live at the Isle of Wight lp?

Daniel Gallagher: On the Isle Of Wight album we’re looking to release the full concert in the setlist order but I’m not sure yet whether this will be part of a DVD package or as a stand alone release.

Shadowplays: Are we any closer to getting the Isle of Wight video released then? What has been the biggest stumbling blocks with that?

Daniel Gallagher:The biggest stumbling block is the amount of vested parties and their varying degrees of interest in the project happening. Murray Lerner ,the film director, and Strange Music are in agreement to make the film but the latest issues are who owns what rights to the audio, but I’m hoping to start actual editing work on it very soon.

Shadowplays: I remember whining to Murray Lerner a few years back that I wanted to see a ‘Taste at the Isle of Wight’ documentary before I died. I’m not getting any younger, Daniel!

Will the entire Taste catalogue be reissued? Any more Taste video out there? I recall Ulster TV doing a special on Taste called, “An Evening with Taste”, and wouldn’t Montreux have videotaped Taste’s appearance too? Sad to think of all the television footage that has been erased, damaged or lost. Still, just when you think you’ve seen all there is, something new crops up. That clip of Taste at the ’69 Essen Pop & Blues Festival was a pleasant surprise, despite the unusual directorial style.

Daniel Gallagher: Getting some Taste audio released for next year is on the agenda, it’s a different scenario for us than the solo Rory stuff where we come up with the idea for the next release and take it to Sony / Eagle Rock. Taste as a band is ‘owned’ by Polydor so we have to wait for them to want to do something but things are looking positive for possibly a 4CD set for next year.

We’ve been searching for Taste footage everywhere, sadly the ‘Evening with Taste’ UTV no longer has and we’ve checked with Montreux and they don’t think the concert was filmed as they have no tapes of it. It’s amazing the random clips that turn up such as the German old man shooting the poster of Taste and the recent find you sent me from the Essen Festival. Hopefully somewhere out there is a full Taste concert, focused solely on them.

Shadowplays: Something else that merits a deluxe offering is Rory’s performances at the BBC — both audio and visual. The two disc BBC Sessions that Donal compiled is one of my favorite albums, but there’s much, much more from their archives, isn’t there? Not to mention the video from his performances at the Hammersmith Odeon and Middlesex Polytechnic!

Daniel Gallagher: The beeb are pretty good, we’ve had good dialogue with their archive and licensing team and they actually sent us masters of all the footage they have. In the main it’s only what has been broadcast before so sadly no extra hour of unseen material etc but we can really work on the audio and visual so it’d be far better than the VHS copies that are currently on youtube. Then I’d need to go through all the audio concerts and sessions to see the magnitude of the set and then see which of our label partners would want to do the release and whether it’s an audio and visual set or two separate releases etc.

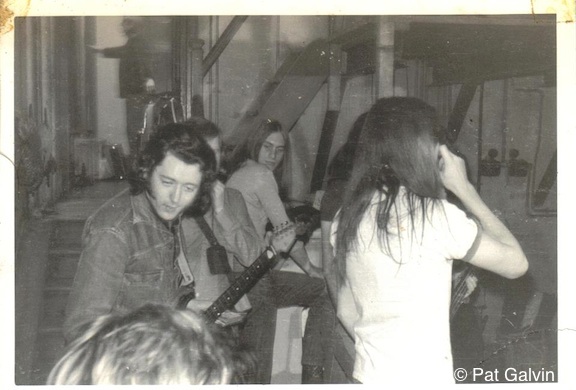

Shadowplays: Sounds like we got some good things to look forward to, Daniel! Thanks for all your hard work with this latest release, the IT ’74 deluxe edition; it’s a wonderful addition to the Rory catalogue, and we look forward to more releases in the future. And let’s give a quick shout out to Andy Pearce and Matt Wortham for a wonderful job mastering the extended IT 74, and Pat Galvin and Eric Luke for some excellent photographs that were included in the IT ’74 booklet!